Corridors of learning

Published on April 16, 2017 | by nst.com.my

NO! My heart sank when it was announced that the Penang State Museum and Art Gallery would be closed for two years for a RM20 million restoration. It seems there are plans in the pipeline to move all the artefacts and temporarily house them at the museum’s Macalister Road branch in George Town. It was with a heavy heart that I made the decision to pay my favourite haunt a visit.

Farewell visits never fail to make me see the same things in a different light. I guess when we‘re conscious that time is no longer a luxury, we try to savour every minute of it. There’s a sense of calm when I arrive at the museum.

Having had my ticket inspected, I proceed to look at the two bronze wall plaques which I’ve always ignored during my previous visits. The inscriptions list the names of the people who’d donated generously towards the Penang Free School building fund in 1816.

Continuing to read the explanatory card beside them, I discover that this Penang Museum building was the original site of the school before it was relocated to Green Lane in 1927. Inspired by the thought that the school spent an astounding 110 years at the very place I‘m standing, I decide to find out more about the early history of Malayan education.

EARLY EDUCATION

Although Penang Free School holds the record for being the country‘s oldest learning institution, education in Malaya didn’t start with the arrival of the British in 1786. Before Francis Light first set foot on the island, Penang’s population already consisted of nearly a hundred Malay fishermen and farmers from Sumatra, Kedah and Satun.

They settled largely around the Batu Uban, Jelutong and Dato Kramat areas.

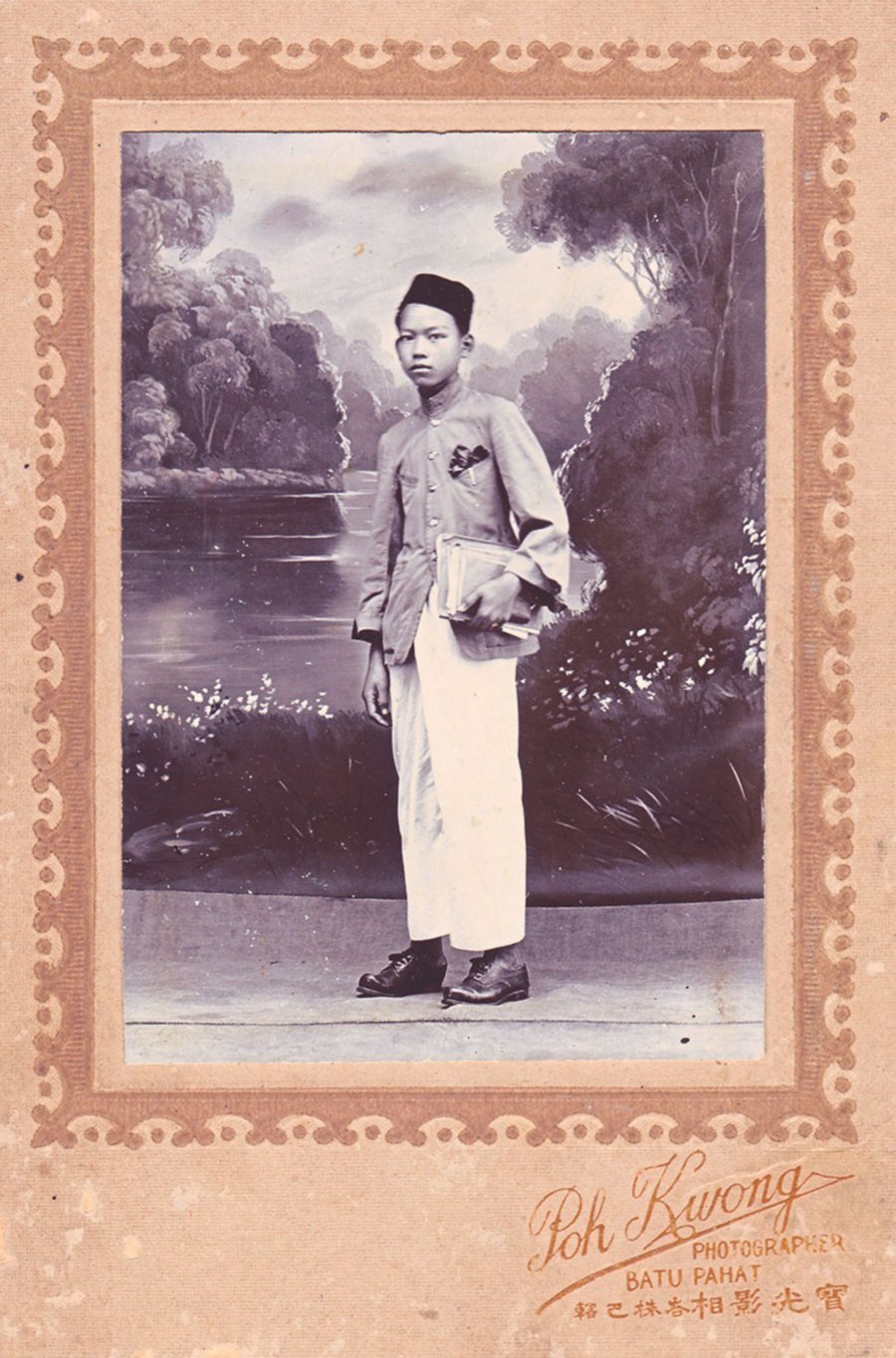

Religious schools are believed to have already existed in the 18th century. Back then, it was common practice for young Malay boys to uproot and live with a renowned teacher for a certain number of years.

They helped the teacher with household chores and at the teacher’s orchards and fields in exchange for lessons in Arabic as well as in reciting the Quran. Malay girls received religious lessons from their parents at home.

Discipline during those early days was very strict and the teachers had the blessings of the parents to mete out punishments as they deemed fit as long as they didn’t mortally wound the children.

At this juncture, I’m reminded of the great Malay scribe Munshi Abdullah. He gave a vivid account of his personal experience in his autobiography, Hikayat Abdullah.

It seems that Abdullah led an early pampered life living with his grandparents. Everything changed when his father found out about his 7-year-old son’s inability to read and write. In a fit of anger, he sent Abdullah to the Kampung Pali Koran School.

Abdullah wrote that all students, regardless of their family background, were treated equally. His teacher resorted to using various “instruments of punishment and torture” to maintain order. Among these was the Chinese press made from four pieces of threaded smooth rattan.

This instrument, known also as apit Cina, was used to squeeze the fingers of boys guilty of stealing or beating their fellow students.

Harsher punishments were meted out on disrespectful students and those who attempted to play truant. Students guilty of these were hung up by both hands so that their feet didn‘t touch the ground.

Pepper was rubbed into the mouths of students who told lies or used foul language. I cringe at the thought of what parents would do to the teachers if such corporal punishments were implemented in schools today.

CHINESE EDUCATION

Within minutes, I reach my favourite section of the museum. The ornately-carved Peranakan household items and the images of early Chinese immigrants paint a vivid picture of what life must have been like for these people who braved the treacherous South China Sea in search of a better life in Malaya.

Back in the early 19th century, formal Chinese education was almost non-existent. Bread and butter issues and survival in a new environment were the main concerns of the “sin kheks”. These new arrivals, comprising mainly of men, lived in cramped and squalid quarters and worked tirelessly from dawn till night.

Many wasted away into oblivion when they succumbed to the temptation of opium. However, a fortunate few managed to avoid this scourge. They worked hard, saved every cent and became extremely wealthy. These successful businessmen brought their wives from China and started their families in Malaya.

Early Chinese education in Malaya began with simple writing schools where boys were taught to copy and memorise the teachings of great Chinese sages. At that time, this training was enough to give them the basic knowledge to help out in their fathers’ businesses.

Older boys were sent to China to continue their studies. While no expense was spared for boys from wealthy families, the same couldn’t be said for girls.

Young Chinese girls were not given any education at all. Parents at that time believed that daughters didn’t contribute to the family’s success.

They leave once they get married. After that, her duty is to her husband’s family. Because of this archaic thinking, many women remained illiterate for the rest of their lives.

WESTERN-STYLE EDUCATION

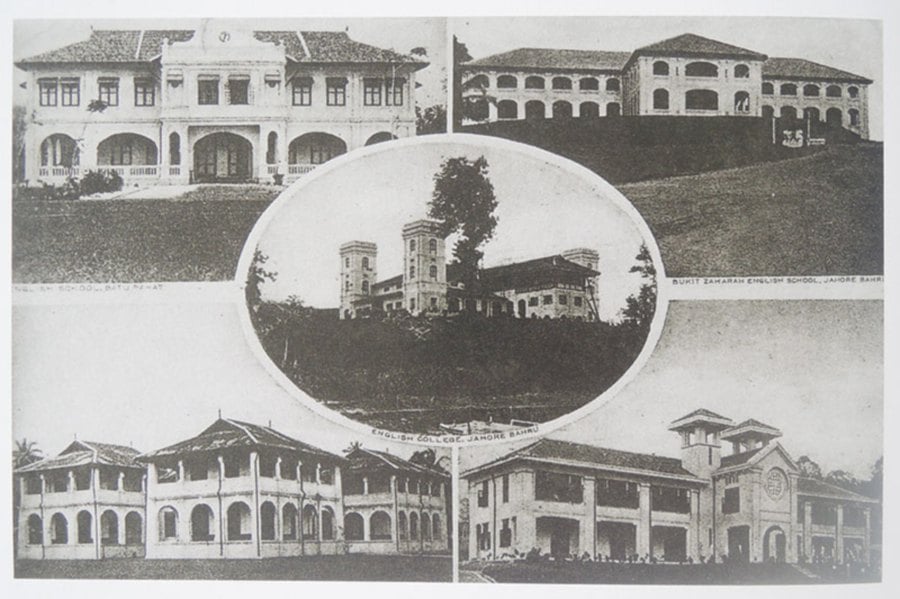

Things slowly began to change with the arrival of the missionaries once the British started ruling Malaya. They began opening up English and vernacular schools in the Straits Settlements.

The Malacca High School and St Xavier’s Institution in Malacca and Penang respectively are good examples. Missionaries, mainly from the London Missionary Society, gained a foothold in the Malay States when the Pangkor Treaty was signed in 1874. These religious men and women brought with them the concept of Western-styled schools where a variety of subjects like reading, writing and arithmetic were taught.

The opening of these missionary schools was a historic moment for education in Malaya. For the very first time girls were given the opportunity to stand head to head with boys in their pursuit of knowledge and self improvement.

Among the first to embrace this novel concept were the Peranakans who were considered the most loyal among British subjects in the colony. For this they gained the nickname of either the Queen’s Chinese or King’s Chinese, depending on the gender of the British monarch at that time.

Judging from the wealth of literary material on display in the museum, it’s probably safe to deduce that the Straits Chinese used education to their full advantage. Learning English in school and speaking Baba Malay at home helped them communicate with almost every segment of society in Malaya at that time.

Trusted by the British, the Peranakans soon gained prominence in the shipping and banking industries. Their stranglehold on these two important segments and commerce gave them immense influence and wealth. Wealthy Peranakan ladies were always seen covered from head to toe in gold and precious stones.

Moving from gallery to gallery in the museum, I began to understand how the introduction of Western-styled education had led to Malaya’s rapid development. A good case in point is the Penang Free School concept. I’d always thought that the word “Free” meant that students were not charged any fees to attend school. I was wrong.

Malayans were introduced to the “Free” concept with the establishment of similar schools which allowed admission to students from all ethnic and religious backgrounds. Right from the beginning these novel educational centres became cultural melting pots where students could mix freely among themselves.

Apart from the main lingua franca of English, these schools also offered multilingual classes in Malay, Cantonese, Tamil and Teochew to further encourage enrolment. Over the years, however, the number of dialect-speaking students steadily declined. This lacklustre response soon led to the abandonment of the multilingual classes, leaving English as the only medium offered.

NEW EDUCATION FRAMEWORK

Malaya continued to prosper during the early decades of the 20th century, which subsequently resulted in a large influx of immigrants into the country. Despite this rise in the number of Indians and Chinese, the colonial government in Malaya stood

by its long-term policy of only recognising

the Malay vernacular language. This resulted in very little or no government funding at

all for schools teaching Chinese and Tamil languages. These schools had to depend heavily on fundraisers and donations

from wealthy members of their own community.

Despite the funding and attention given, Malay parents had little interest in sending their children to government schools. Many were worried that their children would ignore their religious education.

Even those who allowed their children to study in English schools would quickly take them out as soon as they’d acquired the minimum requirement to qualify for a job.

During the 1930s, students could become clerks or even junior teachers once they completed Standard III or IV education.

It was on the eve of Merdeka that the government adopted the Razak Report as the education framework for independent Malaya. The report drafted by Tun Abdul Razak called for a national school system with a uniform national curriculum regardless of the medium of instruction.

Soon after Merdeka, most of the Chinese, Tamil and Mission schools began accepting government funding.

The afternoon spent at the museum has been most “therapeutic”. As I walk back to the bus stop to head home, my spirit is lifted somewhat.

Looking on the bright side, perhaps there will be more fascinating exhibits when the Penang Museum and Art Gallery throws open its doors to the public in 2019.

But until then, it’s farewell Penang Museum. Till we meet again!