On a quest to preserve disappearing Malaysian heritage food

Published on July 5, 2020 | by nst.com.my

“WE just got restless!” exclaims Datin Kalsom Taib, her hearty chuckle slicing through the late morning calm. Colourful butterflies flit gaily around the blooms dotted around her beautifully-landscaped garden in Taman Tun Dr Ismail, Kuala Lumpur, and there’s a gentle breeze in the air.

Seated across from Kak Chom (as she’s fondly referred to), smiling serenely, is her first cousin, Datin Hamidah Abdul Hamid or Adek, the chef.

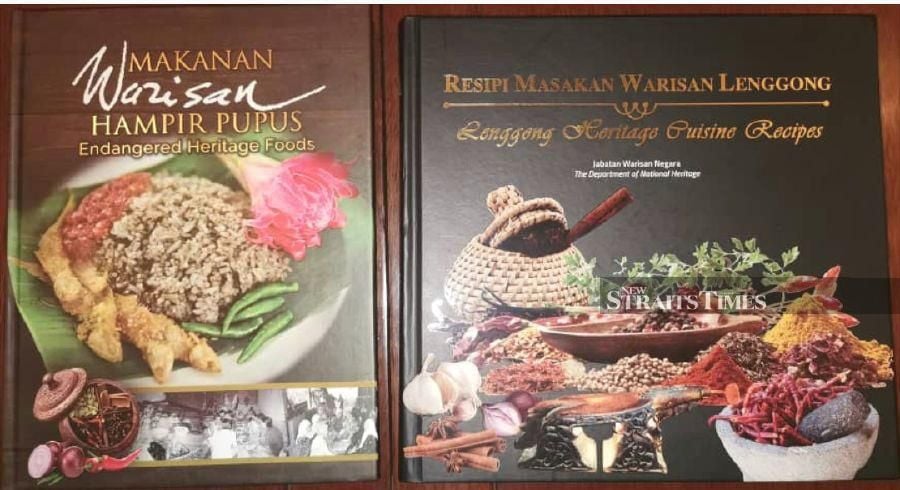

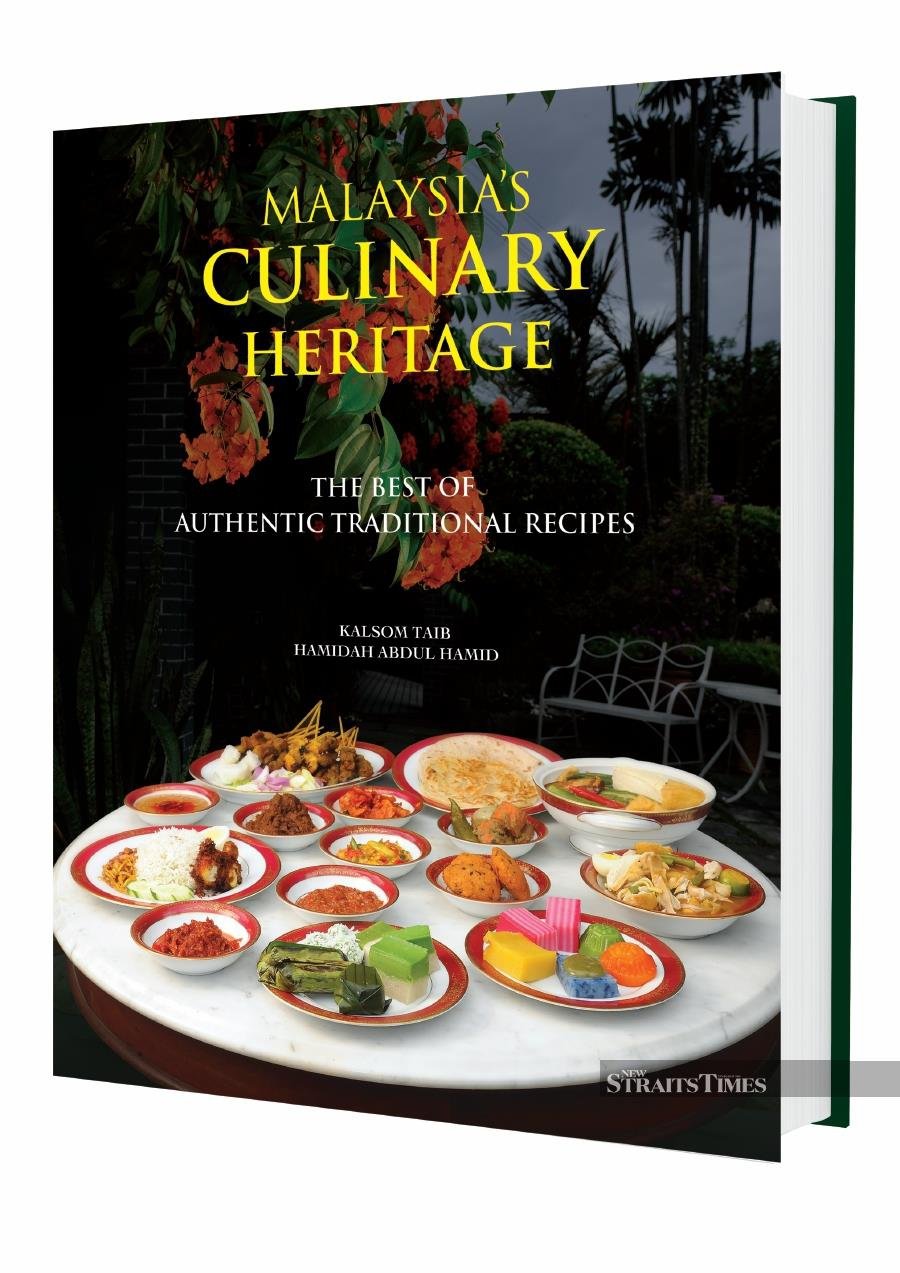

The ladies — both proud Johoreans and hailing from a long line of talented cooks — are the authors behind the recently published Malaysia’s Culinary Heritage: The Best of Authentic Traditional Recipes, a compendium of heritage dishes from around the country.

Dedicated to their respective mothers, Puan Sri Zainab Ahmad and Datin Zaleha Ja’afar, this impressive full-colour tome highlights the 213 dishes (complete with recipes) gazetted by the Department of National Heritage as traditional foods under the National Heritage Act 2005 (Act 645), a move designed to stem the disappearance of dishes which were once firm favourites of our ancestors.

In addition to the 213 items, a further 17 were added in by the authors, in the belief that these (additional) dishes also fulfil the criteria set to qualify (Incidentally, the Department of National Heritage is in the midst of preparing documents on Malaysian Culinary Heritage/Malaysian Heritage Food in order to nominate the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanities to Unesco).

The 230 dishes and recipes are presented in six chapters, segmented accordingly and illustrated with beautiful pictures, covering dishes that accompany rice for everyday meals, to different ways of preparing rice; noodle specialties from the various states to breakfast favourites; right to delightful cakes, desserts and snacks, concluding with a selection of refreshing drinks.

“Like I said, we started becoming restless — sometime last year,” continues Kalsom, evidently the more gregarious of the two.

“We tasted sweet success in 2015 when our maiden cookbook outing, Johor Palate: Tanjung Puteri Recipes, won top honours in the culinary heritage section of the Best in the World Gourmand World Cookbook Awards in Yantai, China, triumphing over eight countries.”

With the success of Johor Palate, a compilation of 240 recipes showcasing the unique flavours and textures of Johor’s heritage cuisine as well as its diversity, the duo found themselves caught up in a whirlwind of book signings, cooking demonstrations at home and abroad, a TV series as well as cooking for corporate and private functions.

A growing demand for a Malay version of the book led them to eventually releasing Citarasa Johor: Resipi Tanjung Puteri the following year.

“But then the lull came and I wanted to do something. Adek was the same. But we didn’t quite know what it was that we wanted to do,” recalls Kalsom, who’s not only a food connoisseur but also an avid writer who has penned biographies on her father (the late Tan Sri Taib Andak), mother (Zainab Ahmad) and husband (Datuk Shafee Yahaya).

Chips in the soft-spoken Adek: “We thought about doing a simple recipe book; something like makanan hari hari (everyday food), cheap everyday fare…”

“But that was until we read about the Congress on Heritage Food, kan Adek?” nudges Kalsom, as Adek nods enthusiastically.

The inaugural Kongres Makanan Warisan held last year and organised by Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) was aimed at raising awareness on Malay heritage cuisine.

It was through her reading of an article on the event that Kalsom learnt about the 213 dishes that had been gazetted by the Department of National Heritage.

“That discovery piqued our interest,” recalls Kalsom, adding that she immediately placed a call to the Department to arrange for a meeting.

“When we finally got to meet, the Department was kind enough to furnish us with the list. I remember asking them whether any book had been produced as a result of the list. None! The only books to have come out were in Bahasa.”

True to form, Kalsom, who’s known for her boundless energy, decided to embark on a new adventure, with Adek the chef in tow, of a second cookbook; this time going beyond their beloved home state to include the whole of multicultural, multi-ethnic Malaysia.

A RIDE TO REMEMBER

A sudden bustle not far from where we’re seated leads to a pause in our chat. A quick glance at my watch reveals that it’s already way past lunch time.

“Eh, makan, makan dulu ye (please eat first),” hollers Kalsom to a small group from the Department of National Heritage, led by Junaidah Salleh, head of the Custom and Culture branch, who’s also here to document the authors’ story.

From the corner of my eye, I can see a long table by the patio laden with food. It seems that our generous host has prepared a veritable feast for lunch.

“We’ve made our famous Laksa Johor, Kuih Lopis (a classic Malay kuih made from glutinous rice, coated with freshly grated coconut and drizzled with thick palm sugar syrup) and there’s also bread pudding and more,” the motherly Kalsom reels off, making me salivate at the thought.

“Faster continue with the interview and then you can eat,” I mumble to myself, sensing the beginning of a rumbling tummy.

Reluctantly tearing my eyes away from the happy bustle, I smile to the ladies, but not without first noting the look of bemusement in Kalsom’s eyes.

“Ohhh, you’ll love our Laksa Johor. EVERYONE loves it!” she exclaims mischievously.

Returning to our book chat, Kalsom shares that Johor Palate took them three years to complete — from the research stage, to recipe testing and finally, the actual writing. This latest undertaking, confides Kalsom, only took seven months.

“I guess after having done the first book, we’d become more experienced and knew what we needed to do. I remember when our recipes got turned down by our editor (for Johor Palate) because of the inconsistencies in measurements,” she recalls, chuckling goodnaturedly. Today, they’ve got both measurements and methods down pat!

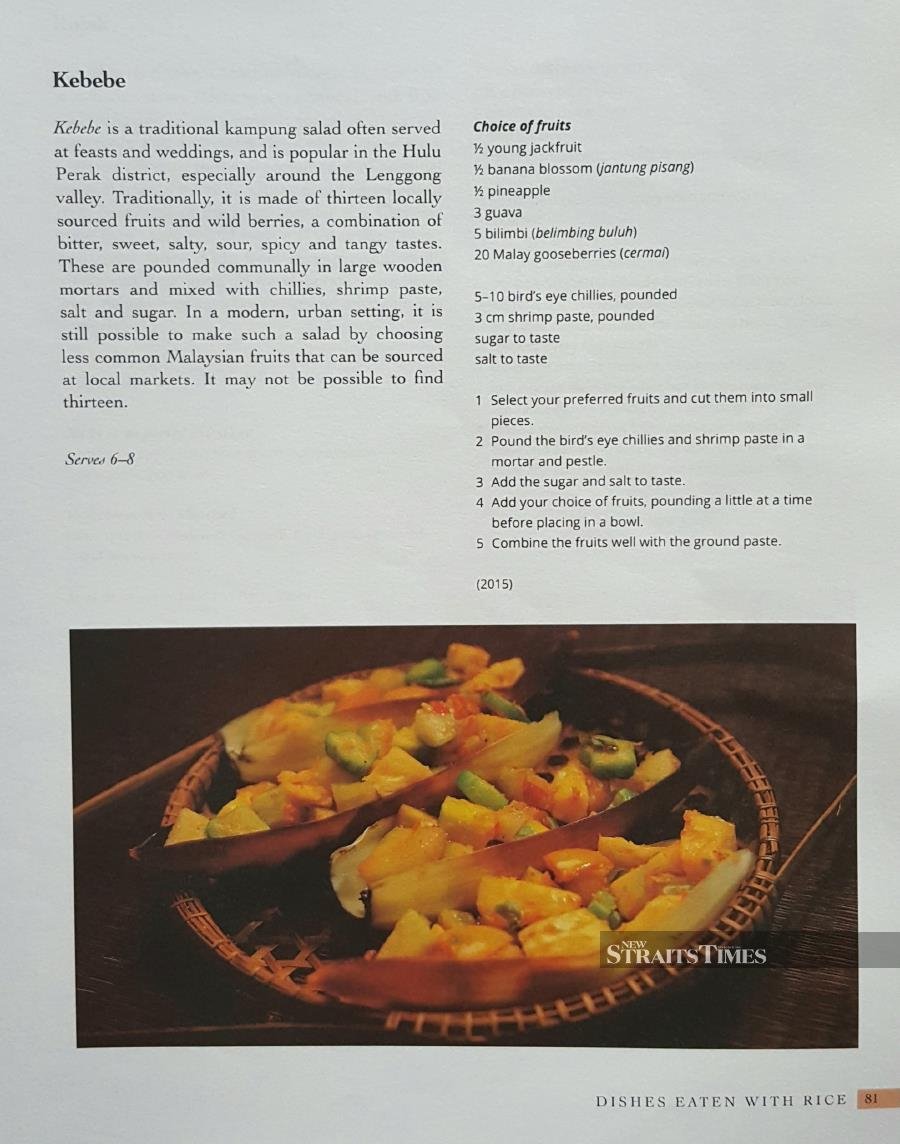

Asked what has been their biggest challenge with this latest book, the ladies concur that it’s trying to work out what some of the “alien” items were. “Kebebe? What’s that?” exclaims Kalsom, feigning incredulity.

She duly learned that this heritage food was actually a traditional kampung salad that’s often served at feasts and weddings, and is popular in the Hulu Perak district, especially around the Lenggong valley. Traditionally, it’s made of 13 locally-sourced fruits and wild berries.

Then there was Tompeh/Tinompeh, she adds, eyes lighting up in delight at my perplexed expression.

“It’s the staple food of the Bajau people in Sabah,” explains Kalsom, elaborating: “It’s made from grated tapioca that’s fried until it becomes yellow. It replaces rice as an accompaniment to savoury dishes.”

“I made it for the photography,” chips in Adek, before pointing to a picture of it in the book’s dummy spread out on the table.

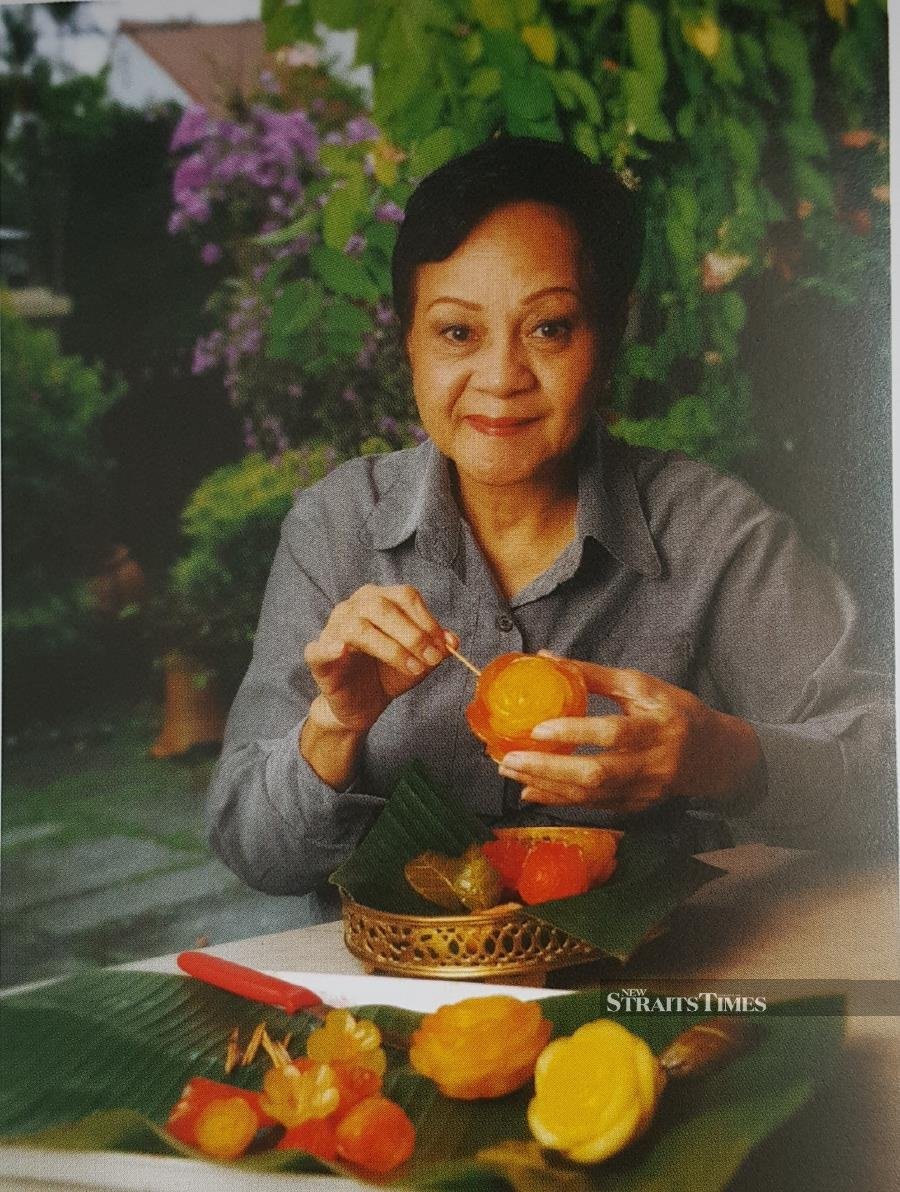

Adding solemnly, the elegant mother of six says: “We can’t just take people’s recipes as is. I need to test everything (the recipes) to make sure that it all works and taste as they should.”

Nodding enthusiastically, Kalsom, a touch of pride lacing her voice, declares: “Adek is the sort that can eat — or even just look at something — and automatically knows what the ingredients are. I wouldn’t be able to tell. That’s why she’s in charge of all the testing and quality control. Her words are final!”

The ladies admit that they didn’t actually try and test ALL the recipes compiled in the book.

“Almost 30 or 40 of the items that made the heritage list and gazetted were already featured in our Johor Palate book. For example, the Laksa Johor,” elaborates Kalsom.

OUR FOOD, OUR IDENTITY

Doing this book was yet another pleasant — albeit challenging — journey of discovery for the affable duo.

Not knowing what some of the “disappearing” heritage food were meant that they had to undertake considerable research, which also constituted going around meeting people and asking for their recipes.

“For example, Yong Tau Foo (a Hakka Chinese dish, which literally means ‘stuffed bean curd’). Subang Golf Club has very nice Yong Tau Foo. I actually asked the chef there to share with me the recipe and he did. But of course, there was no way that Adek was going to let it pass before testing it first,” says Kalsom.

And it was a good thing that she did. The version that Adek created, recalls Kalsom, turned out to be more delicious. “And so it went on. We got somebody’s recipe for the Portuguese Baked Fish and Adek did the taste test. Then there was also someone’s Rendang Tok recipe.”

“Tak sedap pun. Rasa macam ubat! (Not nice. Tasted like medicine)” exclaims Adek, scrunching her nose at the recollection. “You know, doing rendang doesn’t need to be so strenuous. Although I don’t actually keep recipes, I know full well what the taste should be like. So that’s what I try to conjure.”

Nodding, Kalsom chips in: “I’m certainly not a cook or a chef. I can cook la but I need to use recipes. But Adek… she can do without. Just taste and she automatically knows what needs to go in. I remember telling Adek, whatever she does, she must ensure that even I can understand. Everything needs to be exact and kept simple. That way, our readers wouldn’t struggle when they try the recipes from the book.”

What the ladies essentially did was to compile the recipes and reformat everything.

For example, one of the first things they did was separate items into categories — rice dishes together, noodles on one side, desserts and sweets on the other, and drinks at the end. And when there’s 230 food (and drinks) items to trawl through, it was no mean feat.

If there’s one thing they would have liked to see more of, is a greater Malaysian “flavour”.

Explains Kalsom: ‘You might get the sense it’s predominantly a collection of Malay heritage food. But that’s because the bulk of the items gazetted by the Department of National Heritage comprised a large number of treasured Malay dishes. However, we did make the effort to include a number of Indian and Chinese favourites too.”

Take Chapter 4 of the book, titled Breakfast Favourites for example. Here, the authors have gathered what they consider to be some of the most flavoursome breakfasts in the country. The items range from predominantly Malay rice-based dishes to Chinese-style congee (porridge) and noodles to Indian breads.

“The selection is by no means complete as there are many more items, particularly from Sabah and Sarawak, and the east coast of Peninsular Malaysia, that we weren’t able to include,” concedes Kalsom, before adding that the recipe for one popular breakfast dish from the east coast, Nasi Dagang, does make an appearance in Chapter 2.

Collectively, writes Kalsom, the culinary traditions of Malaysia’s various ethnic groups form a proud national heritage, a legacy of early trade, settlement by diverse peoples and a blend of past and modern influences.

These are the flavours of Malaysia, a delightful mixture of traditional dishes that continue to be appreciated by all Malaysians and which thoroughly deserve to be preserved for posterity.

One of the reasons why food and eating occupies such a central position in multicultural gatherings in the country is because it allows everyone to enjoy our diverse food culture.

“It’ll be a sad day when some of these traditional dishes are no longer served,” says Kalsom solemnly, her kindly face wreathed in lines of worry.

Adding, she declares: “There really is a compelling need to, therefore, leave a legacy that can be enjoyed by future generations of Malaysians.”

Suffice it to say, for the ladies, the biggest satisfaction they derive from taking on this latest “project” — all 320 pages of it — is the knowledge that they’ve also played their part to leave something for the future generation.

“You know,” says Kalsom, her voice low, “This book can become a family heirloom, passed down from generation to generation so that our heritage foods will continue to be made and live on. It’s truly a tome to treasure.”

Like a famous French gastronomist once said, “Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are.”

There’s never a more apt quote to illustrate just how much food truly does construct our identity.

THE ARMCHAIR COOK AND THE CHEF

As I leisurely leaf through the giant dummy of the book, enjoying the light caress of the breeze in the lovely garden, I ask the ladies to tell me more about themselves.

Having met them back in 2015, again for an interview — on their maiden cookbook outing — I recall that the lively Kalsom is somewhat of a historian.

“Yes, I used to teach history,” exclaims the graduate of the University of Malaya, who taught in secondary schools for five years before joining the private sector. In the 1970s to 1990s she worked in several multinational corporations, including Shell Malaysia, Malaysia Mining Corporation Bhd (MMC) and Nestle Malaysia.

“I was in the Human Resource department of Shell for 11 years, and then with MMC as head of HR for 10 years,” begins Kalsom, offering me an insight into her career trajectory. “And then Nestle lured me to join their Human Resource team and there I stayed — for seven years — until my retirement.”

Chuckling, Kalsom confides: “Nestle had a kitchen and I got involved. I remember always asking my boss if I could do one of his shows. I wanted to go on TV to do a cooking show. Although he didn’t allow, I still managed to follow him whenever he took the shows outside of the country!”

Turning to Adek, Kalsom says fondly: “Adek is my first cousin. An entrepreneur with a passion for cooking. Do you know that exclusive Adek Boutique at Istana Hotel in KL was one of her first ventures? Very famous in the 80s!”

Apologising for digressing, Kalsom returns to her story of how the two first got together to combine their talents — hers for writing, and Adek’s for food.

“Adek was doing a recipe book. I was doing a recipe book but just of simple recipes for my children. I was compiling my mother’s recipes actually.”

Adek came to the house for a visit. Recalls Kalsom: “She said to me, ‘Abang Chom (Johorean term), you publish books. How do you do a book?’ and then she showed me her recipes. I told her I was also working on a book. Of course, there were many similarities in our content because we share the same ancestors.”

As Kalsom was not a cook and Adek was not a writer, the idea to combine their respective expertise and produce a book together was born.

“I would write and Adek would be the chef. That’s how we formed our partnership. I always say, we are each other’s right hand, left hand. She needs me, I need her. The two of us clap together!”

Proudly, Kalsom shares that Adek, who was also in the business of wedding planning, gift shop and food and hamper business in the past, is a naturally gifted cook.

“Her mother, her grandmother, her mother-in-law were all great cooks,” she says, turning to Adek, pride lighting her eyes.

“Our family is a family of cooks,” chips in Adek, her voice gentle. “Our grandfather’s nickname was Tok Selera, given by the Palace. He was a senior civil servant with a good palate. He employed Chinese, Indian and Malay cooks. So it’s no surprise that we can do what we do.”

Shyly, Adek, who was married off at the age of 20 and thus was unable to pursue further studies after her Higher School Certificate examinations, adds: “My daughters can cook really well too!” The girls — Idah Ayu Natalia and Idah Aiman Safuraa — actually assisted their mother in the cooking and testing of the recipes in this tome.

In fact, Malaysia’s Culinary Heritage eventually ended up being a family affair. Even Kalsom’s grandchildren were roped in and they assisted their grandmother in the research and the typing of recipes.

Meanwhile, their respective husbands, Datuk Shafee Yahaya and Datuk Ibrahim Ismail, became their food tasters!

Just like the Department of National Heritage, both Kalsom and Hamidah (Adek) are fully aware that the consumption of Malaysia’s heritage food is seeing a decline due to globalisation. In fact, the authenticity of our heritage food is under threat from “glocalisation”.

Indeed, this is a timely initiative by the duo in the drive to preserve and increase the acceptance level of our heritage food among the new generation.

Even though Malaysia is synonymous for being a food paradise, offering a wide range of local and international cuisines, it’s imperative that the heritage foods of each of her region and ethnicity are able to sustain their uniqueness in order that their quality can be preserved for generations.

As they say, heritage food forms one of our common links as Malaysians. As such, they should remain an integral part of our lives. And never be allowed to disappear or be forgotten.