How a 1911 cholera outbreak helped improve Msia’s health services

Published on December 25, 2019 | by nst.com.my

KUALA LUMPUR:THE unfortunate news of a 3-month-old boy from Tuaran, Sabah, who recently contracted the polio virus has shocked many people.This stemmed from the fact that the vaccine-preventable disease was Malaysia’s first case in nearly three decades after it was eradicated.

Malaysia’s last polio case was reported in 1992, and in 2000, our country was declared free from the life-threatening and potentially crippling disease.

In the wake of the Sabah incident, those from the medical fraternity have renewed calls to make vaccination compulsory for Malaysians.

According to the Malaysian Medical Association, the immunisation schedule, which includes the vaccine to prevent polio, is free for all citizens and contains a list of recommended immunisations from birth to 15 years of age.

While the call to make the National Immunisation Programme mandatory is timely, it also highlights a series of cholera outbreaks in Alor Star during the early part of the 20th century that led to heightened health awareness in Malaya.

FIRST BRITISH ADVISER

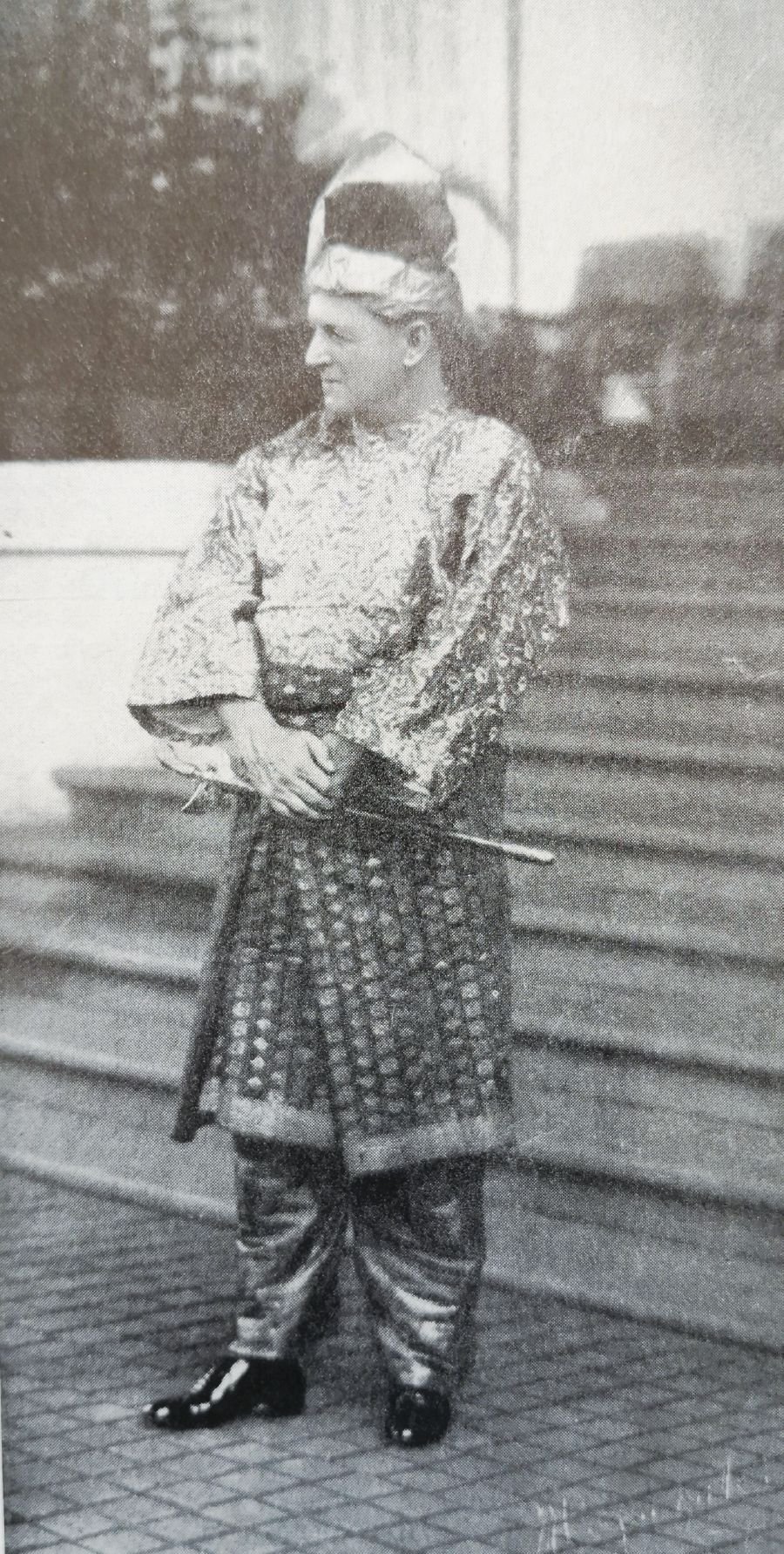

George Maxwell arrived in Alor Star on July 15, 1909 to assume duties as the first British adviser to Kedah following the transfer of suzerainty of the four northern Malay states from Siam (now Thailand) to Great Britain.

With the ruling monarch Sultan Abdul Hamid Halim Shah incapacitated by prolonged illness, Maxwell was met at the wharf in Jalan Pengkalan Kapal by Tunku Mahmud Tunku Ahmad Tajuddin Al-Mukarram Shah, president of the State Council, and W.J.F. Williamson, financial adviser to the former Siamese government.

During his tour of the state capital, Maxwell was alarmed to learn that the town did not have a consistent supply of clean water.

After discovering that the people depended solely on Sungai Kedah and Sungai Anak Bukit for their daily water consumption, the third generation Malayan civil servant knew that something had to be done.

Five months later, Maxwell convinced Tunku Mahmud and State Council members to award several contracts to bore deep holes in strategic locations around Alor Star.

Unfortunately, his effort to obtain clean water from the ground had to be abandoned after the project was mired by delays.

Unperturbed by the setback, Maxwell spent the following year looking for other options through consultations with engineering experts in other parts of British-ruled Malaya.He was evaluating several shortlisted proposals when his worst fears became a reality.

CHOLERA STRIKES

In early 1911, Alor Star was struck by severe floods that brought about a cholera outbreak.The waterborne disease spread to Kulim, Krian, Kuala Muda and Kepala Batas via flood victims who abandoned their inundated homes and sought refuge with relatives.

Maxwell and the State Council members were quick to respond to the calamity.

They established the Alor Star Sanitary Board to improve health standards and end the outbreak.

Despite deaths and hardship experienced by the people, some good did come out of the epidemic. The state government started to pay attention to the need to supply clean water to Alor Star residents.

On Sept 8, 1911, the Straits Times reported that Penang Municipality engineer L.M. Bell had been commissioned to estimate the cost of supplying the state capital and a large part of the Kedah coastal region with drinking water brought in by pipes from Bukit Wang, a hilly region 33km north of the capital.

After conducting a study, Bell presented his report to the Kedah government. Apart from suggesting that a substantial amount of investments was required, he cautioned that the project would need about three years to come to fruition.

MANDATORY LEGISLATION

Fearing that history might repeat itself, the state government passed Enactment No. 124 (Vaccination) in 1913, which required all children, including those born from that year onwards, to be vaccinated free of charge.

The law meted out harsh penalties to ensure compliance. Those who contravened the strict inoculation order were liable to a maximum fine of $250 or three months’ jail.

The Kedah royal family was among the first to respond to the legislation. The sight of medical officers at the palace, however, struck fear into the hearts of Sultan Abdul Hamid’s children, including Tunku Abdul Rahman Putra Al-Haj, who was 10 at the time.

Tunku tried to elude the vaccination by escaping via the kitchen exit, but was caught by his mother’s servants and brought to his grandmother’s room where he joined his siblings in the inoculation process.

Although vaccination was a great success in Alor Star, the same could not be said about rural areas where strong apprehension towards Western medicine was exacerbated by nonchalant attitudes.

DEATH AND EVACUATION

As a result, those living in villages were hard hit by contagious diseases when floods returned to Kedah in early 1914. The situation fell to a new low when Europeans, who had better access to health services in the state, were also affected.

On Feb 2, 1914, the Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser reported that the cholera epidemic had claimed the life of Kedah assistant auditor general A.G.W. Ward three days earlier.

Ward, who had served Kedah for 18 years and was due to return home, died at Alor Star General Hospital 10 hours after contracting the disease.

Further gloom was cast over Kedah when news broke that the state surgeon and superintendent of prisons, Dr A.L. Hoops, and his wife had also been infected.

Although both were expected to pull through, their two children were taken to the British adviser’s residence in Bakar Bata and placed under the care of Maxwell and his wife, Florence Stevenson.

The grave situation in Kedah prompted aid to arrive from neighbouring states. Within days, the colonial steamer Seagull transported Dr Hall Tennant and a nurse from Penang General Hospital to Alor Star and evacuated healthy Europeans to Penang on its return trip.

Cholera slid into the background and became a rare occurrence when the taps started flowing in November 1914. The homes of European and Malay officials were the first to enjoy this convenience. Standpipes were erected in the streets of Alor Star for public use.

IMPROVING HEALTH SERVICES

Maxwell’s reputation as a person keen on improving public health, particularly through preventive measures, preceded him after he left Kedah in 1919 to serve as the British resident of Perak for two years.

Health services in Malaya began to improve by leaps and bounds in 1920 when Maxwell became chief secretary of the Federated Malay States (FMS) of Selangor, Negri Sembilan, Perak and Pahang.

Apart from directing the Medical Department’s health branch to begin sanitary inspections of schools and ordering the establishment of town dispensaries, Maxwell set up three Advisory Committees to deal with venereal disease, infant welfare and tuberculosis.

Venereal disease was first treated on an organised scale at Kuala Lumpur Hospital in 1923.Following the success of the first venereal disease clinic that was established in Sultan Street in July 1924, more clinics were opened in Ipoh, Taiping, Seremban and Klang.

By 1930, there were six clinics and 53 treatment centres throughout the FMS. The number of patients rose annually to 40,802, with prostitutes forming a significant portion of women seeking treatment.

Due to gender imbalance among Chinese migrants, male members of this community suffered the most from the disease compared with their counterparts from other races.

Before 1920, infant mortality in the FMS was extremely high, amounting to one out of four live births. The principal cause was malnutrition of mothers combined with other diseases and complicated by cholera, dysentery and diarrhoea.

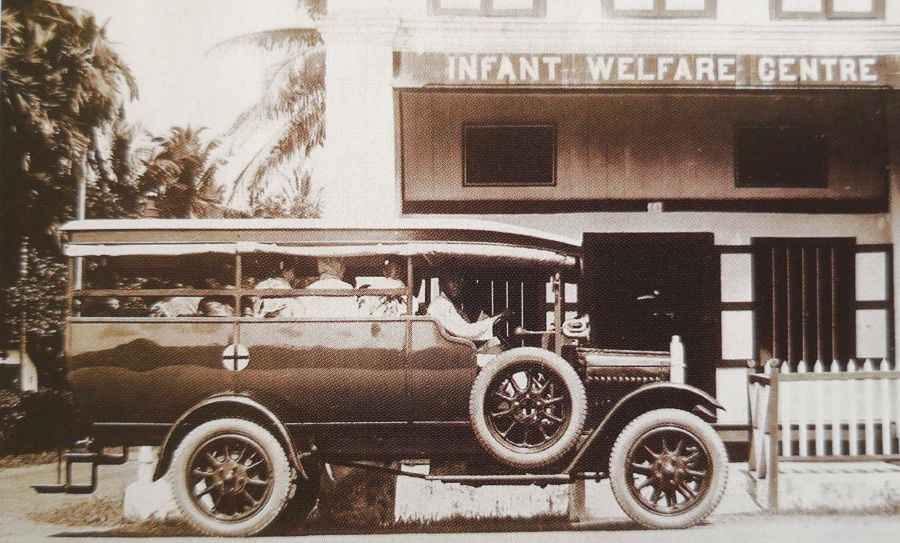

Survival rates began to improve with the establishment of Infant Welfare Centres in Kuala Lumpur,Ipoh, Taiping and Seremban. The centres were supervised by women medical officers, who were assisted by European sisters and local nurses.

In Kuala Lumpur, a motor bus was purchased to transport women and children from remote areas who were too poor to pay for the journey to the centres.

At the same time, nurses regularly visited homes of newborns, and conducted health checks on infants and their mothers, as well as provided free supply of medicines. Milk and nutrient-rich food that they brought along were sponsored by private companies.

Improvements initiated by Maxwell must have inspired Dr Hoops to contribute more to Malaya’s health services as he left Kedah in 1924 to head the Medical Department in the Straits Settlements as principal civil medical officer.

CHANGING PUBLIC PERCEPTION

Similar to cases in Kedah, Dr Hoops discovered that many locals were reluctant to make use of government hospitals due to reasons like the distrust of Western medicine, poor diet, long travelling distance from home, absence of relatives and friends and rumours of staff abuse, bribery and neglect.

The challenge that Dr Hoops found most difficult to face was the inability to change people’s perception that hospitals were houses of death. He learnt that patients were reluctant to seek treatment in hospitals until it was too late for doctors to do anything about their conditions.

Apart from locals, hospitals also received complaints from expatriates.A controversy erupted among Europeans in 1927 when a visiting committee reported that Penang General Hospital was a disgrace and human lives were endangered by dilapidated buildings, inadequate staff, as well as unsatisfactory and outdated equipment.

The committee, which consisted of prominent British Penang residents, resigned en bloc when Dr Hoops said it had overstepped its authority by making damaging entries in its report.

The scandal ended only when the government announced that the hospital would be rebuilt to meet higher standards.

Although health services in Malaya continued to improve long after Maxwell and Dr Hoops left the Malayan civil service upon their retirement in 1926 and 1930, respectively, it cannot be denied that they played important roles in the advancement of public health, especially in their pioneering work on Kedah’s cholera vaccine administration more than a century ago.

Although vaccines are recognised as one of the greatest achievements of biomedical science, more needs to be done for them to reach their full potential in preventing the spread of infectious diseases.

Apart from gaining public trust and acceptance of vaccines, the authorities must monitor the borders to control the entry of infected persons and adhere to the principle of universal health coverage where no one is left behind.

More stories

>>> GO: Reliving Kedah’s ancient past

>>> 37 Tempat Makan Menarik Di Alor Setar | Restoran Best Untuk Foodie

>>> Malaysia-North Korea ties symbolised by rice museum

>>> New reign for an ancient dynasty

>>> Old-new history of ancient Kedah

>>> Exploring Alor Setar In Kedah, Malaysia

>>> Always Be Ahead with Maxis | Langit Collective Farms Opportunities for Communities