A Secular Islam Possible for Malaysia?

Published on January 2, 2024 | by Dr Lim Teck Ghee

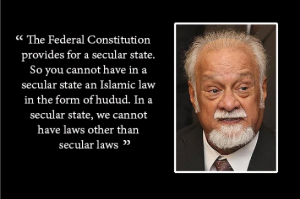

The recent PAS Muktamar brings to the forefront – yet again – the question of whether secular Islam is a possibility in an increasingly racially and religiously acrimonious and divided Malaysia.

Secularism has been defined as the separation of public life and civil/government matters from religious teachings and commandments, or more simply the separation of religion and politics. It is an evolution that the great majority of the world’s nations have gone through – some quickly, others more slowly.

However, almost all nations, even as they develop at uneven speeds, have inevitably gravitated towards a separation of religion and state.

Today, except for a few countries such as Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Iran and Yemen, most nations – developed and developing – view a religiously-based state as a throwback to a more primitive form of government; and a historical era in which life was nasty, brutish and short, except for the religious elite.

Secular states in which governments are neutral in matters of religion and public activities, and where the states’ decisions are not dictated or influenced by religious beliefs, are the opposite of theocratic states.

At the same time it needs to be noted that not all secular states are alike. Thus we find states with a comprehensive commitment to secularism; those that are more accommodating to religion; and others that, although committed to neutrality, will selectively actively cooperate with religions.

Whatever the degree of secularity, secular states, except those which morph into totalitarianism or autocratic systems, are committed to the implementation of national and international norms protecting the freedom of religion or belief, and abide by constitutions which guarantee the equal treatment of different communities of religion and belief within society.

In sharp contrast the theocratic state has a God or a particular deity to be the supreme civil ruler. Also the God’s or particular deity’s commandments are held to be the definitive law of the land; and the authorities and their representatives who interpret the commandments claim a superior or divine duty in running the affairs of state and society.

Debates on merits ongoing, but no poll held

Debate on the relative merits of theocratic and secular states has been ongoing for several hundreds of years in both Muslim and Christian worlds. In our era, a poll of the world’s foremost leaders – including religious – on what they may view to be a superior form of government – secular or theocratic – has never been held.

The Late Karpal Singh is right but when he was Prime Minister, Tun Dr. Mahathir had the audacity to claim that Malaysia is already an Islamic state, while his successor promoted Islam Hadhari and Najib Razak embraced Hadi Awang’s Hududism and Zakir Naik. As a result, the Malays have become a confused people.–Din Merican

But if one were to be undertaken today, I will not be surprised if the polled group of religious leaders – despite their concerns about the negative impact that a sharp break separating public life from religion could have on their congregations – will agree that a secular state is the correct path to progress and a better life for their religious communities.

I expect too that few among the religious leaders would want a return to the days when there was a fusion of religious and political authority, even if they may personally benefit from the shift of power in society.

For, make no mistake about it, history – past and current – is replete with examples of how theocratic states, even after co-opting or hijacking secularised concepts of equality and justice, have invariably lapsed into religious tyrannies with dire consequences for all of the citizenry.

As Thomas Paine, one of the founding fathers of the United States noted, “Of all the tyrannies that affect mankind, tyranny in religion is the worst; every other species of tyranny is limited to the world we live in; but this attempts to stride beyond the grave, and seeks to pursue us into eternity.”

The crisis in Malaysia

Secular Malaysia today is facing a crisis with Muslim politicians from both sides of the political divide seeking to strengthen conservative Islam through castigating its moderate and liberal proponents, and by making the case that supporters of a secular Islam are kaffirs, traitors and enemies of the religion.

The situation has become so bad that few Muslims in the country are willing to take a public stand on the issue or declare support for secular Islam for fear of reprisal by religious extremists.

The sole exceptions that have stood out have been non-political figures, such as Mariam Mokhtar, Noor Farida Ariffin and some other members of G25, Syed Akbar Ali, Marina Mahathir, Haris Ibrahim, Din Merican, and Farouk Peru, and an even smaller number of politicians, notably Zaid Ibrahim and Ariff Sabri.

One sees in their messages to fellow Muslims in this country some of the same concerns that are animating liberal and secular Muslims in other parts of the world, viz:

- The rejection of interpretations of Islam that urge violence, social injustice and politicised Islam;

- The rejection of bigotry and oppression against people based on prejudice arising from ethnicity, belief, religion, sexual orientation and gender expression;

- Support for secular governance, democracy and liberty; and

- Support for the right of individuals to publicly express criticism of Islam (see ‘Muslim Reform Movement’ by M Zuhdi Jasser and Raheel Raza et al).

Unfortunately, these messages – partly because they are communicated in English and partly because the mainstream Malay (and English ) media have chosen to ignore them – are unable to reach the Malay masses – whether in rural or urban communities. They have even failed to elicit support from the unknown number of open-minded and liberal Muslims who are now openly branded as “deviants” by Islamic religious authorities.

In the Malay world, it is Malay politicians and the Islamic elite and bureaucracy who have a monopoly over the variant of Islam that is propagated to the masses. It is a variant that is currently feeding on heightened ethnic and religious insecurities and jealousy, so as to make it much more difficult, if not impossible, to have a rational discourse on secular Islam, save that advocated by Umno and PAS.

LIM TECK GHEE is a former World Bank senior social scientist, whose report on bumiputera equity when he was director of Asli’s Centre for Public Policy Studies sparked controversy in 2006. He is now CEO of the Centre for Policy Initiatives.

Lim Teck Ghee

Lim Teck Ghee PhD is a Malaysian economic historian, policy analyst and public intellectual whose career has straddled academia, civil society organisations and international development agencies. He has a regular column, Another Take, in The Sun, a Malaysian daily; and is author of Challenging the Status Quo in Malaysia.

Lim Teck Ghee PhD is a Malaysian economic historian, policy analyst and public intellectual whose career has straddled academia, civil society organisations and international development agencies. He has a regular column, Another Take, in The Sun, a Malaysian daily; and is author of Challenging the Status Quo in Malaysia.