Taiping’s everlasting heritage

Published on April 28, 2019 | by nst.com.my

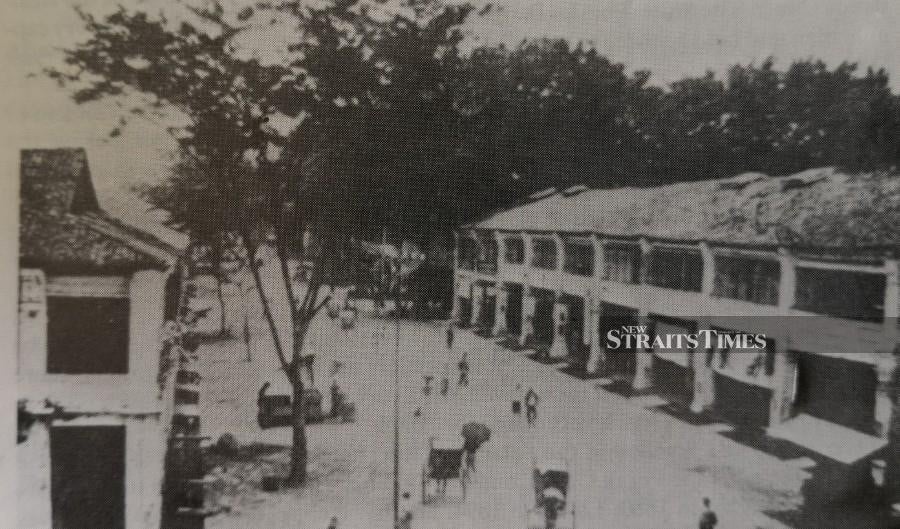

TAIPING’S grand dame of buildings isn’t a stately hotel or an ornate government office frequented primarily by the rich and powerful.

It’s actually a very public one that has been visited almost daily by every layer of society for more than a century.

A survivor of two great economic depressions and just as many world wars as well as countless local strife, the former Perak capital’s central market is today the proud holder of two enviable records.

The building, built sometime between 1884 and 1885, is Malaysia’s oldest market as well as the largest free-standing non-religious wood-and-cast iron structure in the country.

Recent news of plans by the local authorities to restore and transform this historic structure into a food and souvenir market has been well received by all quarters.

It’s about time that the pride of Taiping receives just rewards after serving the local residents loyally for some 135 years.

Curious to know more about what life was like in Taiping during those early days, I head for the nearest public library in town for an afternoon of research.

Contrary to my expectations, there are not many references related to the early history of this town. Most literature uncovered is about the tin rich Kinta district which is located south of Taiping.

Nevertheless, nuggets of interesting information start to surface soon enough and, within the hour, I embark on a most exhilarating journey back in time.

Starting at a point about a decade before the very foundations to the famous market were erected.

BIRTH OF TAIPING

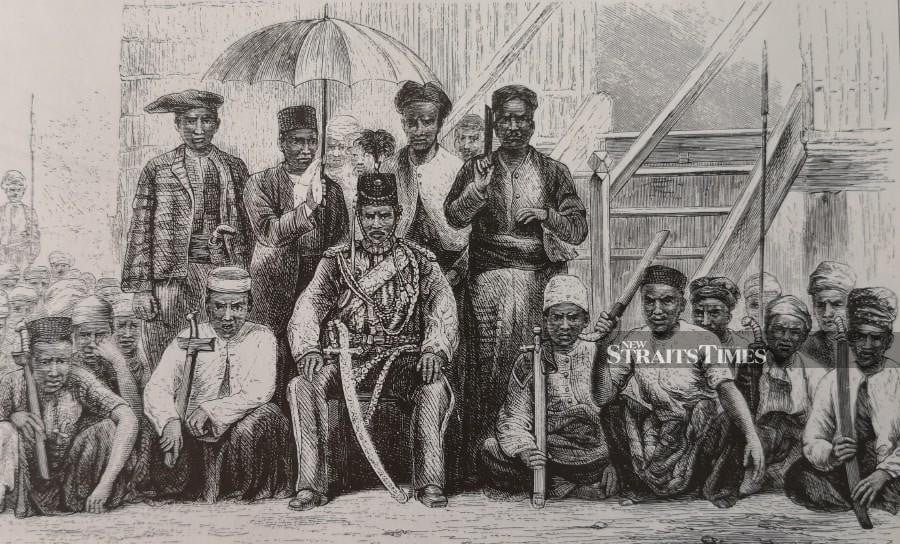

Taiping’s rise from obscurity began soon after the British gained a foothold in Perak on Jan 20, 1874.

Soon after Raja Abdullah and several Malay chieftains signed the now famous Pangkor Treaty, James Wheeler Woodford Birch, Colonial Secretary of the Straits Settlements made Bandar Bahru in Lower Perak his administrative capital.

At that time, Birch had just been appointed the first British Resident of Perak.

At the same time, Captain Speedy, who was the Assistant Resident, chose to station himself in Larut and began making plans for the establishment of two key towns.

Speedy named the first, Taiping. He chose the name – Chinese for Everlasting Peace – as it conjured thoughts of a happy omen for the future.

The second town set up was Klian Bahru which later reverted back to its original Malay name, Kamunting.

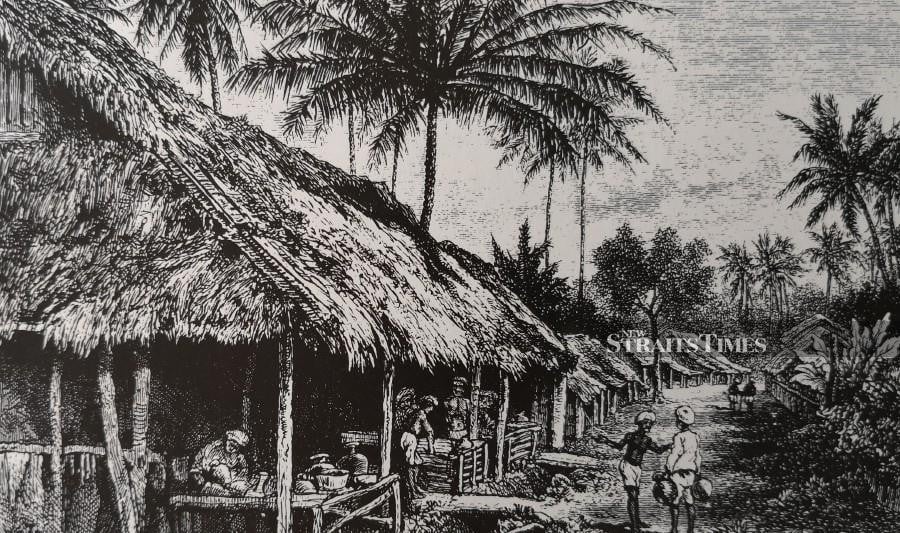

Situated about four kilometres from Kota and near the old mining village of Klian Pauh, Taiping recorded a population size of 5000 by the end of 1874.

A tenth of the residents were shopkeepers who dealt primarily in goods destined for the surrounding tin mines. Duty on tin became the primary source of revenue for Taiping at that time.

In order to encourage growth, agricultural land was given free of any charge or duty.

The people only had to apply to the Sultan of Perak through the British Resident for land and, based on the portion cultivated after a three-year grace period, a grant in perpetuity was given at a nominal fee of $1 per acre.

At that time, however, agriculture was largely confined to rice cultivation by the Malays.

ESTABLISHING CONNECTIVITY

Keen to establish a direct line with Penang, Speedy set about building new roads that joined both Taiping and Kamunting as well as with the road coming down from Province Wellesley.

The corduroy type of roads built then was of inferior quality and required regular maintenance.

They were simply constructed of tree trunks laid down side by side for foundation into swamp land through which they ran for the most part of the distance.

A six-inch layer of clay was then placed on top of the trunks before a final top up with coarse sand.

Parts of the road regularly sank into the ground when the timber foundations gave way to decay due to the extremely damp conditions.

The establishment of government departments grew in tandem with the growth in Taiping.

Key positions like Inspector of Mines, Harbour Master and Treasurer were held by Europeans while the Malays and Chinese held most junior posts.

There was only one Indian in government employment in 1874. Identified with just a single name in the records, Muttusamy worked as an overseer in the Mining Department.

The assassination of Birch on Nov 2, 1875 resulted in a major confrontation between the Malays and the British.

Thanks to its location away from the incident, Taiping became one of the rare beneficiaries of the ensuing upheaval.

By 1877, Taiping was made the new administrative capital of Perak while Kuala Kangsar became the royal town.

EARLY TAIPING

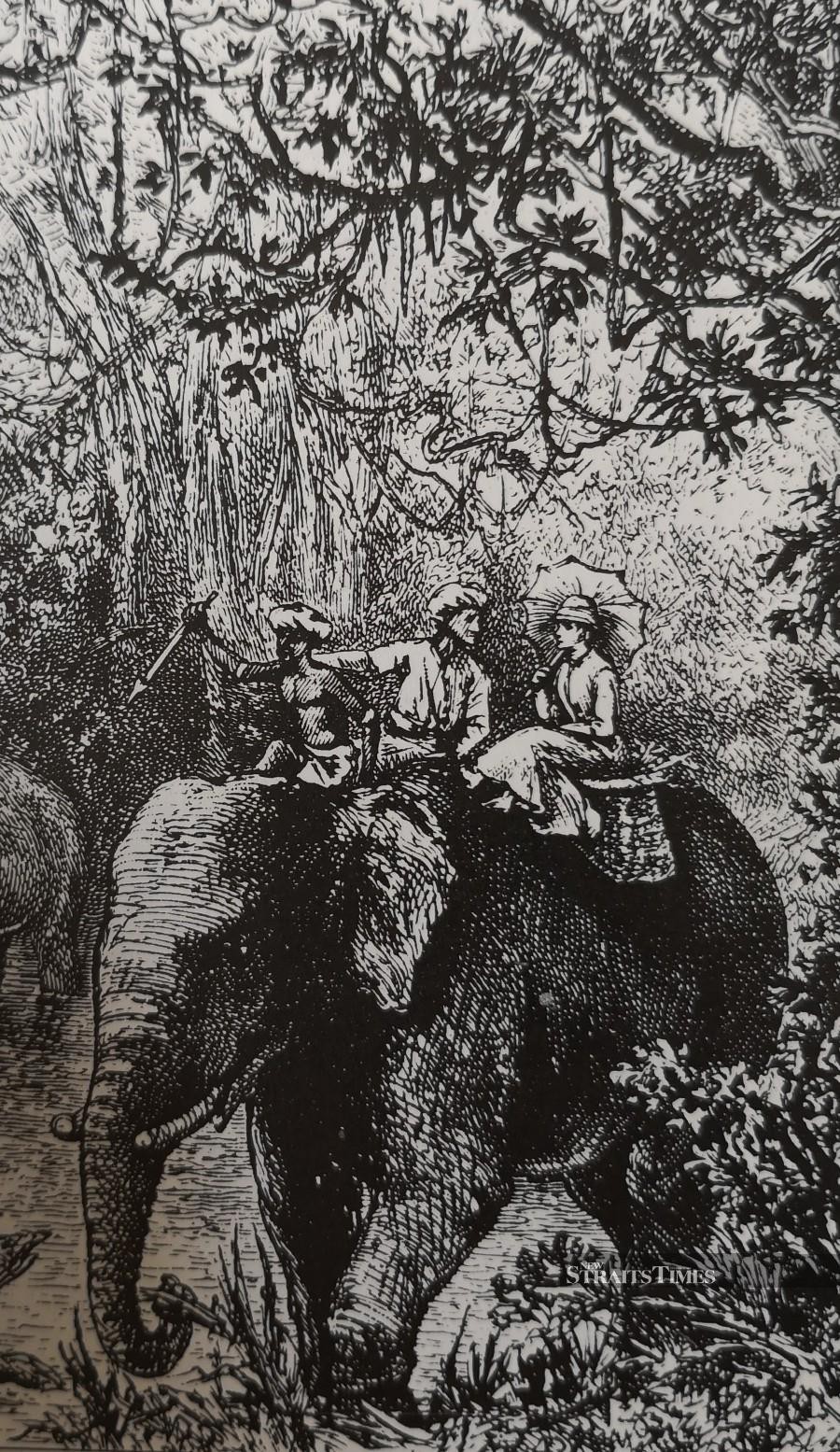

Renowned British explorer, writer, photographer and naturalist, Isabella Lucy Bird visited Taiping in early 1879 during her travels through Malaya.

Excerpts from her book, The Golden Chersonese and the Way Thither, published in 1883, painted Taiping as a fine town with a mile long street filled with bazaars and shops, gambling houses, workshops and meeting halls for the local population.

Bird also noted the presence of a large detached barracks for the Sikh police, hospital, powder magazine, parade ground, government storehouse, gaol as well as neat bungalows for English officials.

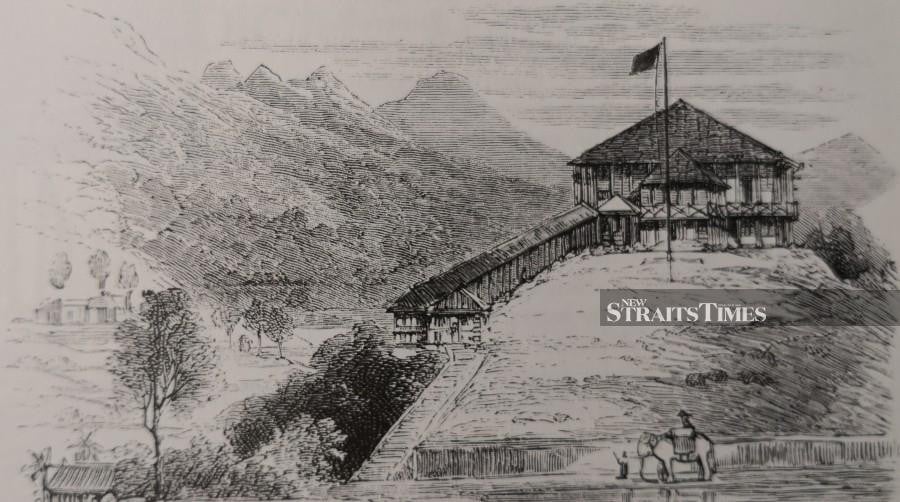

She was most impressed with the grandest building in Taiping at that time – the British Residency which was perched on top of a steep, isolated terraced hill.

Taiping at that time had 6000 inhabitants who were primarily Chinese miners. According to Bird, the town was tolerably empty during the day but came to life at dusk when the miners returned.

She also noted the reasonably good health of the people and attributed that to the existence of the Yong Wa Hospital for paupers which came under the watchful eye of Dr Wright.

Well managed and staffed, the hospital could cater to the needs of 900 patients at any one time.

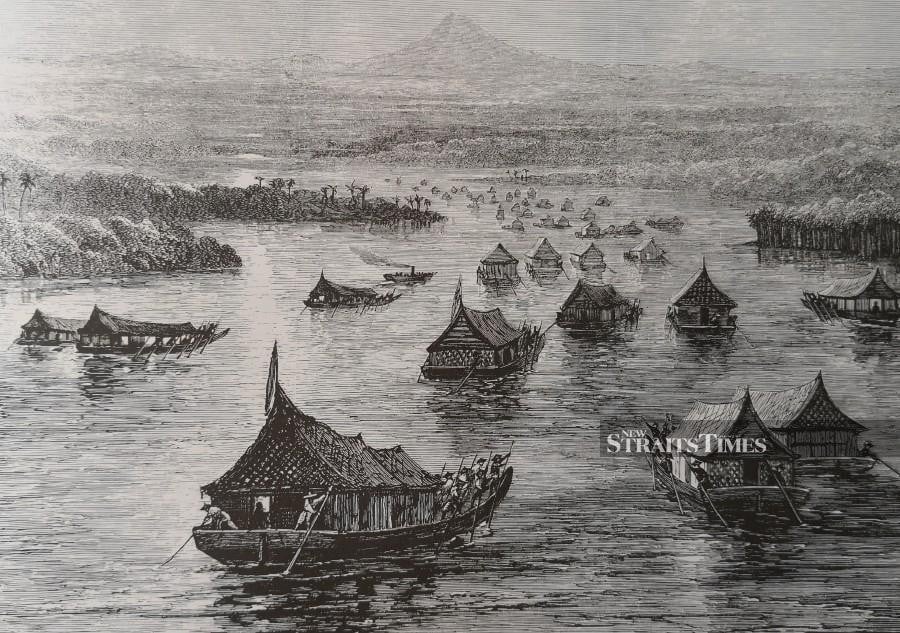

The new Governor of the Straits Settlements, Sir Frederick Weld visited Taiping in the middle of 1881. Impressed with what he saw, Weld suggested the construction of a rail and tramway from Taiping to the port (later named Port Weld in his honour and much later became known as Kuala Sepetang) among the next most necessary works to be undertaken.

MAJOR GAME CHANGER

The construction of the Taiping-Port Weld railway marked the beginning of a major transformation that radically altered the landscape of the Malay Peninsula permanently.

It also brought about the first major influx of Indians and Ceylonese into Perak.

Weld showed great interest in Taiping because of his ongoing pet project, visiting the town twice in April and November 1883 with the hopes of spurring progress as well as to inspect other new developments taking place in the town.

The Governor was particularly impressed with Taiping’s newly completed water works which supplied the purest water from a waterfall in the hills about four kilometres from town.

Despite his impatience, Weld found himself away on leave when the Taiping-Port Weld railway line, the first of its kind in this country, was completed.

Acting Governor Sir Cecil Clementi Smith went on the trial run in his stead on Feb 12, 1885.

Taking a brief breather from reading and copious note-taking, it suddenly dawns upon me that the construction of the Taiping central market coincided exactly with the time of the Taiping-Port Weld railway project.

Surely there must have been smaller markets in Taiping before then but the huge economic boost as well as the significant influx of migrant workers brought about by the railway project would surely have given rise to the need for a larger and better equipped place for people to obtain their daily sustenance.

The large market, measuring 220 feet long and 60 feet wide, had the capacity for traders to bring in fresh produce in large quantities from other parts of the country, including freshly caught seafood, via the new mode of transportation from Port Weld.

Much to everyone’s delight, the faster and more efficient railway together with economies of scale helped to bring down cost of foodstuff sold at the new market significantly.

Fresh buffalo meat went for five or six cents a kati while fish and vegetables bearing the same weight merely commanded 10 cents and 2 cents respectively.

The selling price of a bag of rice was $2.50.

The booming tin trade and growing income gave the people superior purchasing power.

Taiping people were happy as they forked out less for the same amount of items bought before the arrival of the railway.

The excess funds meant that both they and their families could enjoy a better standard of living.

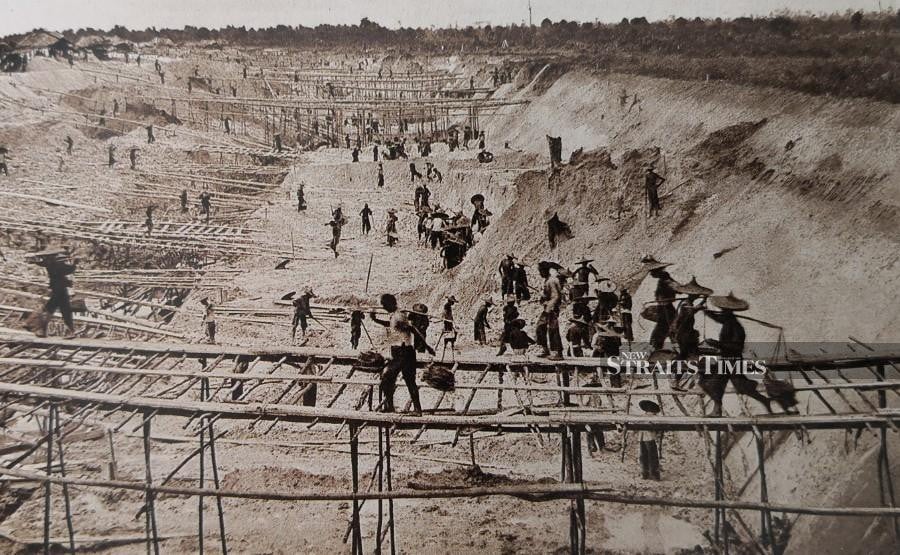

The late 1880s saw Taiping maintaining its position as a busy mining centre that serviced bigger open-cast mines in Assam Kumbang, Kota, Kamunting and Tupai.

These mines employed huge numbers of Chinese migrant workers. It wasn’t uncommon at that time to see individual mines having up to 4,000 workers each.

All the money earned at the mines eventually ended up in Taiping. The abundance of prosperity eventually gave rise to the establishment of revenue farms that operated pawnshops as well as gambling and opium dens.

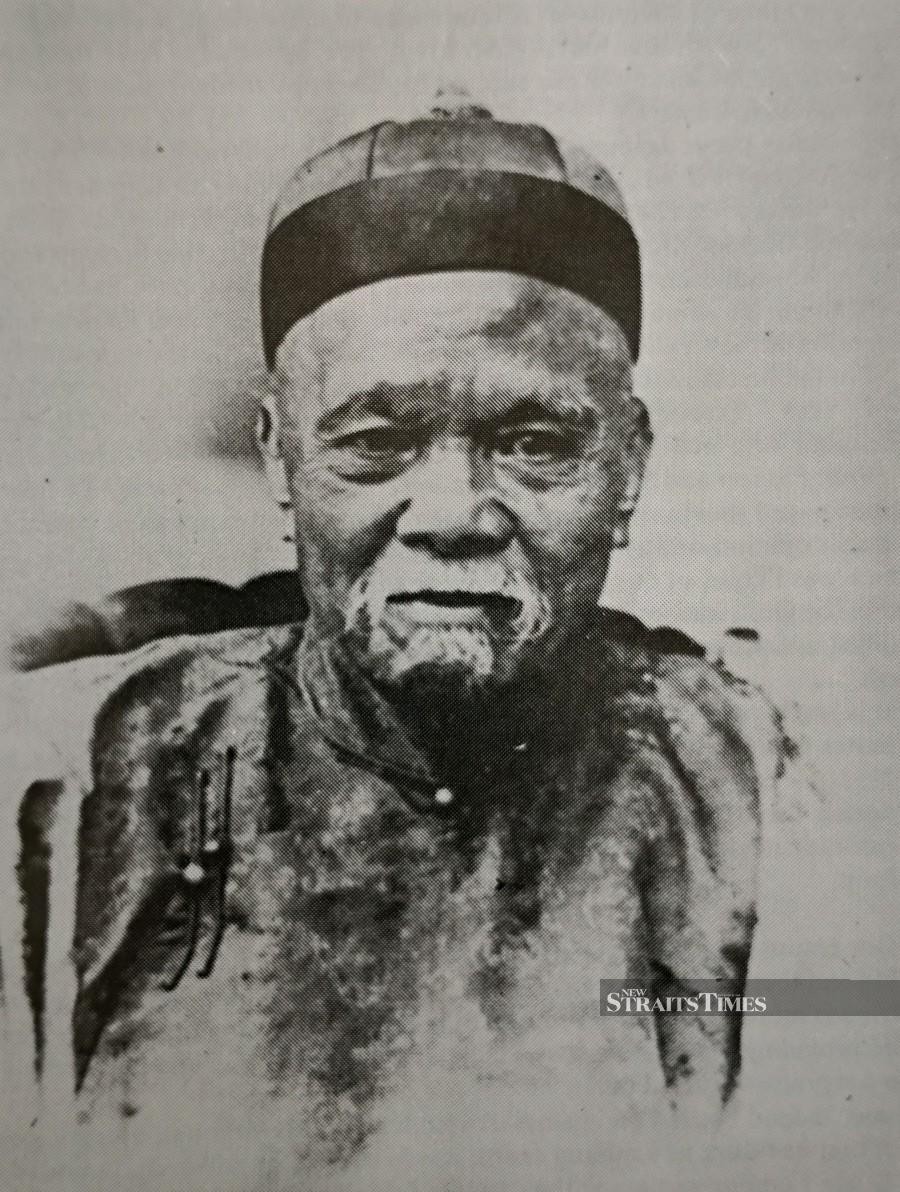

The leading revenue farmer at that time was the Kapitan China himself, Chung Keng Kwee.

END OF AN ERA

Like most things in life, however, the good times in Taiping didn’t last. By late 1894, there were signs that the town had seen better days.

Production at the once-productive Assam Kumbang mines was on a steep decline.

Things were so bad that the gambling house there had to be abandoned almost overnight.

The closure was soon followed by another which used to be the pride of Taiping as it had the rare honour of hosting a visit by King Chulalongkorn of Siam (now Thailand) back in 1889.

The second mine closure put to rest all lingering doubts about the end of an era as far as tin trade was concerned.

Despite the bleak outlook, the town refused to fade into oblivion. Contrary to expectations, Taiping continued to develop thanks to rapid progress brought by the railway and the innovative nature of its residents.

The locals began to gradually shift their focus from tin to agriculture. They experimented with tapioca and sugarcane cultivation.

Interest in the former was short-lived but the latter made rapid progress. By 1898, large swathes of padi land were converted into sugarcane plantations.

European participation saw a marked increase in total sugar exports from Perak, rising from 55,000 piculs in 1890 to 288,000 piculs at the turn of the 20th century.

By 1905, however, the enterprise fizzled out when Taiping began embracing the rubber boom that was taking Malaya and the rest of the world by storm.

Within a decade, large rubber estates like Simpang Estate, Lauderdale Estate and Matang Jamboe Estate began to take shape and, like before, money once again began finding its way to Taiping.

CONTINUED DECLINE

For a while, at least, the decline of Taiping at the end of the 19th century can only be compared in relative sense.

Tin mining around the area continued into the early 1930s but, as a mining centre, Taiping had been upstaged by its southern neighbour, the Kinta district.

The transition was so acute that the prestigious state capital accolade passed from Taiping to Ipoh in 1937.

Taiping’s dire situation was exacerbated by the Great Depression that hit Malaya hard in the middle of 1930s.

Beginning in the United States, the scourge had devastating effects in countries both rich and poor. International trade plunged by more than half and unemployment rose rapidly.

Demand for latex plummeted and many rubber estates around Taiping and all over Malaya suffered severe losses.

Coupled with the devastating effects of the Japanese Occupation that followed soon after and the ensuing Malayan Emergency, Taiping gradually lost its economic clout and was sidestepped by major developments as the years wore on.

Returning the reference material, I come across a recent article heralding heartening news about Taiping’s recognition as the third most sustainable city in the world at the 2019 Sustainable Top 100 Destination Awards at the Internationale Tourismus-Borse Berlin (ITB) travel trade show in Berlin, Germany.

Together with the upcoming RM9 million market facelift, this prestigious international accolade recognised Taiping’s leadership in urban sustainability and avoidance of disruptive over-tourism.

By the looks of things, the best is yet to come for Taiping. Speedy was spot on when he chose to have the word “everlasting” in the name of this wonderful heritage town that will forever be the pride of both Perak as well as all of Malaysia.