Dindings Fort

Published on Nil | by sabrizain.org

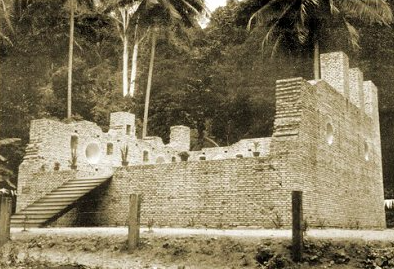

The fort on Pangkor Island is called Kota Belanda (‘Dutch fort’) by local Malays and is located at a place called Teluk Gedung. However, Dutch records referred to it as the Dindings fort (‘Dingdingh’) – named after the Dindings River which it faced on the coast of the Peninsula.

The fort on Pangkor Island is called Kota Belanda (‘Dutch fort’) by local Malays and is located at a place called Teluk Gedung. However, Dutch records referred to it as the Dindings fort (‘Dingdingh’) – named after the Dindings River which it faced on the coast of the Peninsula.

Perak was the main tin-producing kingdom in the whole Peninsula and the Dutch East India Company wanted to control and monopolise its trade, so its ships blockaded Perak for much of the seventeenth and eighteenth century. There was also a strategic reason for this blockade – Perak was nominally a vassal of Acheh and the Dutch was at war with the Sumatran state.

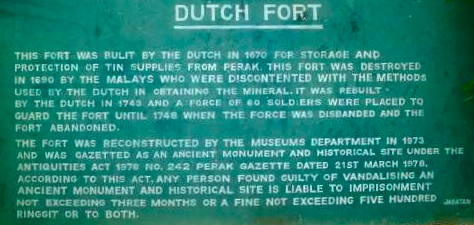

For this reason a Dutch outpost was established at Teluk Gedung in 1670 to support this blockade – and to prevent the occupation of the island by the English, who were by then active trade competitors in the region.

The report of the Dutch Governor Balthasar Bort in 1678 states that “at the present time, 59 men are before Perak, engaged in the blockade of that place and stationed on the island of Dinding, which the Honourable Company has in its possession, occupying a square wooden fort there provided with nine pieces of iron ordnance.”

The report of the Dutch Governor Balthasar Bort in 1678 states that “at the present time, 59 men are before Perak, engaged in the blockade of that place and stationed on the island of Dinding, which the Honourable Company has in its possession, occupying a square wooden fort there provided with nine pieces of iron ordnance.”

The 59 men consisted of a superintendent merchant, a captain, a bookkeeper, three assistants, three second mates, two junior surgeons, eight men-at-arms and 40 seamen, manning the garrision and its small flotilla of the yacht ‘Laren‘, the sloop ‘Cacap‘ and the boat ‘Dingdingh‘.

The fort appears to have been strengthened a few years laters, as British explorer and buccaneer William Dampier describes in 1689: “The Dutch, who are the only inhabitants, have a fort on the east side (of the island), close by the sea, in a bending of the island, which makes a small cove for ships to anchor in.

The fort is built four-square, without flankers or bastions, like a house: every square is about ten or twelve yards. The walls are of a good thickness, made of stone, and carried up to a good height of about thirty foot, and covered overhead, lke a dwelling house.

There may be about twelve or fourteen guns in it, some looking out at every square. These guns are mounted on a strong platform, made within the walls about sixteen foot high; and there are steps on the outside to ascend to the door that opens to the platform, there being no other way into the fort..

Here is a governor and about twenty to thirty soldiers, who all lodge in the fort. The soldiers have their lodgings in the platform among the guns, but the governor has a fair chamber above it, where he lies with some officers.”

“About a hundred yards from the fort, on the bay by the sea, there is a low timbered house, where the Governor abides all the day time. In this house there were two or three rooms for their use, but the chief among them was the Governor’s Dining-Room. This fronted to the sea, and the end of it looked towards the Fort.”

“About a hundred yards from the fort, on the bay by the sea, there is a low timbered house, where the Governor abides all the day time. In this house there were two or three rooms for their use, but the chief among them was the Governor’s Dining-Room. This fronted to the sea, and the end of it looked towards the Fort.”

“The distance between it (the fort) and the river’s mouth is about 4 or 5 Miles; they have also a Guard-ship commonly lying here, and a Sloop with 20 or 30 armed Men, to hinder other nations from this trade…. The Dutch also commonly keep a Guard-ship, and have made some fruitless essays to bring that Prince and his Subjects to trade only with them; but here over against Dinding, no Strangers dare approach to trade- neither may any Ship come in hither but with consent of the Dutch.”

All supplies were brought from Melaka because, according to Dampier, the garrison was in “a continual fear of the Malayans, with whom though they have a commerce, yet dare they not trust them so far, as to be ranging about the Island in any work of husbandry, or indeed to go far from the Fort for there only they are safe.”

All supplies were brought from Melaka because, according to Dampier, the garrison was in “a continual fear of the Malayans, with whom though they have a commerce, yet dare they not trust them so far, as to be ranging about the Island in any work of husbandry, or indeed to go far from the Fort for there only they are safe.”

Dampier describes an incident during dinner when “the Governor, his guests and some of his officers were seated, but just as they began to fall to, one of the Soldiers cried out “Malayans!”. Immediately the Governor, without speaking one word, leapt out of one of the windows, to get as soon as he could to the fort. His officers followed, and all the servants that attended were soon in motion. Every one of them took the nearest way, some out of the windows, others out of the doors, leaving the three guests by themselves!”

“They fired several guns to give notice to the Malayans that they were ready for them; but none of them came on. For this uproar was occasioned by a Malayan canoe full of armed men that lay skulking under the island, close by the shore: and when a Dutch Boat went out to fish, the Malayans set upon them suddenly and unexpected, with their krises and lances, and killing one or two the rest leapt overboard, and got away, for they were close by the shore: and they having no arms were not able to have made any resistance.

It was about a mile from the Fort: and being landed, every one of them made what haste he could to the fort, and the first that arrived was he who cried in that manner, and frighted the Governor from supper.”

“We kept good watch all night, having all our guns loaded and primed for service. But it rained so hard all the night, that I did not much fear being attacked by any Malayan; being informed by one of our seamen, whom we took in at Malacca, that the Malayans seldom or never make any attack when it rains. The next morning the Dutch sloop weighed, and went to look after the Malayans; but having sailed about the Island, and seeing no enemies they anchored again.”

“We kept good watch all night, having all our guns loaded and primed for service. But it rained so hard all the night, that I did not much fear being attacked by any Malayan; being informed by one of our seamen, whom we took in at Malacca, that the Malayans seldom or never make any attack when it rains. The next morning the Dutch sloop weighed, and went to look after the Malayans; but having sailed about the Island, and seeing no enemies they anchored again.”

In 1690 the Dutch garrison was again attacked by the Malays under one Panglima Kulup and the garrison massacred. On 24 June 1693 an order was given that, in consequence of this massacre, no garrison should be posted again at Pulau Dinding but that a stone pillar should be erected there, having on one side the arms of the United East India Company and on the other those of the United Provinces as a token of Dutch possession. In 1695 and 1721 and 1729, orders were issued for the repair of this stone.

On 20 November 1745 Governor-General Gustraaf Willem, Baron van Imhoff ordered the rebuilding of the fort at Pulau Dinding: it was to have a garrison of 30 Europeans and 30 Asiatics (with the provision that they were not Bugis).

On 20 November 1745 Governor-General Gustraaf Willem, Baron van Imhoff ordered the rebuilding of the fort at Pulau Dinding: it was to have a garrison of 30 Europeans and 30 Asiatics (with the provision that they were not Bugis).

Then, according to Malacca records under the date 22 October 1746, an under-merchant, Ary Verbrugge, was sent to Perak to ascertain if the king would allow a fort to be erected up-river and agree to sell all tin to the Company. On 25 June 1747 Sultan Muzaffar Shah III of Perak signed an agreement to deliver all tin to the Dutch and granted permission for a fort to be built anywhere on the estuary.

A Malay history of Perak, the ‘Misa Melayu’, describes how the Dutch fortified a brick factory (gudang) at Pangkalan Halban on Tanjong Putus. This was established on 18 October 1748 and van Imhoff ordered the removal of the garrison from Pulau Dinding to this new fort.

In 1795, when Malacca was taken over by Great Britain, Lord Camelford (then a lieutenant in the Navy), and Lieutenant Macalister proceeded up the Perak river with a small force and compelled Christoffel Walbeehm to surrender the Dutch fort at Tanjong Putus, which in the nineteenth century was broken up by an English Superintendent of Lower Perak to metal the roads of Teluk Anson (now called Teluk Intan)!

A short distance from the Dindings fort is Batu Bersurat (Sacred Written Rock). On this massive rock, drawings of a tiger mauling what is believed to be a child can be found. This large granite boulder has the inscription ‘1743 I.F.CRALO’ and the initials ‘VOC’ (Veerenigde Oostindische Compagnie – The Dutch East India Company), and the image of a tiger.

A short distance from the Dindings fort is Batu Bersurat (Sacred Written Rock). On this massive rock, drawings of a tiger mauling what is believed to be a child can be found. This large granite boulder has the inscription ‘1743 I.F.CRALO’ and the initials ‘VOC’ (Veerenigde Oostindische Compagnie – The Dutch East India Company), and the image of a tiger.

The story behind it is that the child of a Dutch dignitary, who played by the rock, disappeared with no trace and it was presumed that a tiger had taken the child. However the villagers said that it wasn’t the tiger that had taken the boy, but more probably angry Malays, who wanted to rid Pangkor of the Dutch. The Dutch could have also chiseled this incident on the stone depicting the Malays as a tiger.

The National Museum (Muzium Negara) undertook the reconstruction of the Dindings fort in 1973 and was gazetted as a historical monument under the Antiquities Act in 1976.

About the Author Write to the author: sabrizain@malaya.org.uk

The Sejarah Melayu website is maintained solely by myself and does not receive any funding support from any governmental, academic, corporate or other organizations. If you have found the Sejarah Melayu website useful, any financial contribution you can make, no matter how small, will be deeply appreciated and assist greatly in the continued maintenance of this site.