Great Malaysian Railway Journeys

Published on Nil | by great-railway-journeys-malaysia.weebly.com

MALACCA

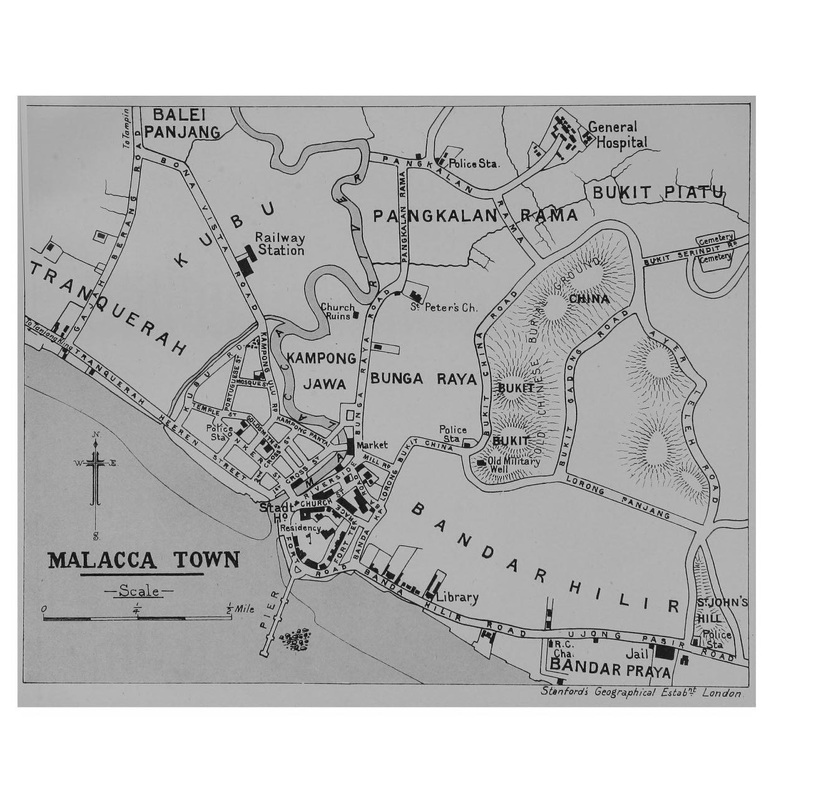

In 1914, it was possible to travel to Malacca (Melaka) by train via the 32km branch line from Tampin to Malacca town which was opened in 1905. The Japanese pulled up the rails during World War II for re-use on the infamous Death Railway in Burma (Myanmar). The line was never rebuilt after the War.

The 1914 Pamphlet of Information for Travellers, Tours in the Malay Peninsula has a lot to say about Malacca.

Here are some of the highlights:

The scenery on that section of the railway which lies between Rembau Station and Malacca is, without doubt, the most beautiful on the whole line, especially the piece between Malacca and Tampin. It is, therefore, a pity to reach and return from Malacca by the night trains, since the views are lost. The road runs alongside the railway most of the way, and is, for scenery, the fairest in the Peninsula. The distant blue hills, the rice-fields, the Malay orchards, every now and then a bright river, or ponds full of lotus provide views which will never be forgotten.

The Malacca railway station no longer exists. The station was located on Bona Vista Road, today’s Jalan Hang Tuah. This photo was taken in its approximate location. The extra wide pavement is probably where the tracks ran.

From the platform are visible the twin towers of the French Mission’s Church and the hill of Saint Paul with its ruined church and signal station. The railway resthouse is alongside the station. Rikishas are the conveyance here and are more suited to Malacca’s narrow streets than gharis. The route to the bridge, whither all traffic from the railway station tends, is past two Malay mosques and up Jonker Street.

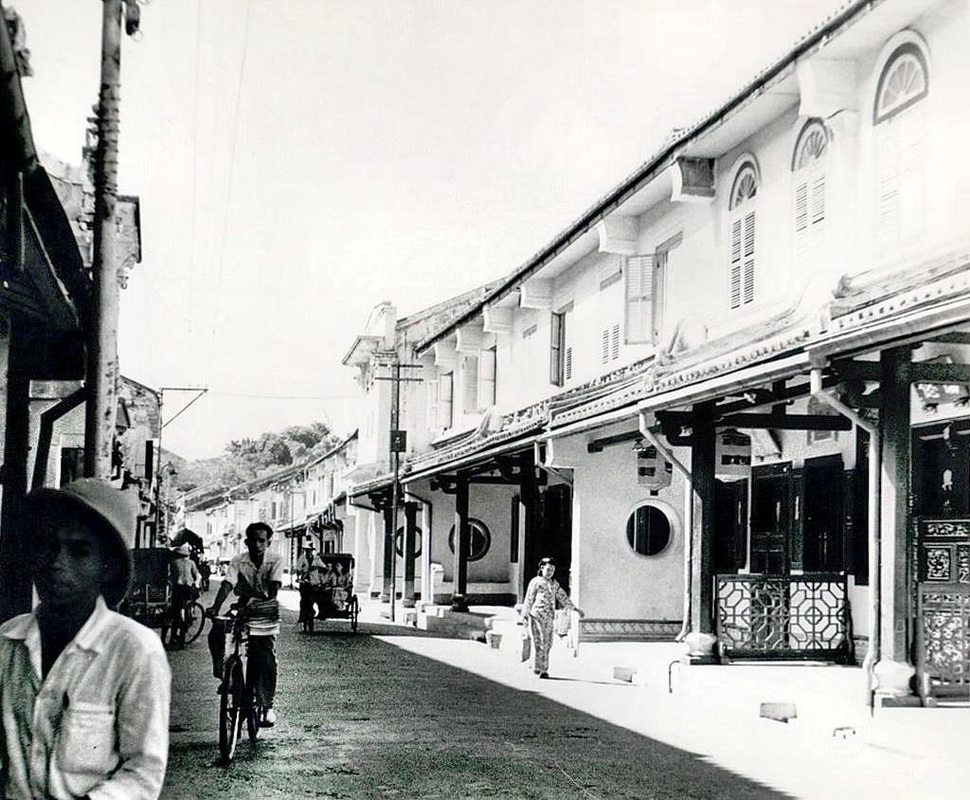

The town is quite small and, except for its curiosity shops, presents few features of interest besides Jonker Street and Heeren Street. Of these the former is a pale copy of the latter. In Jonker Street it is true that the old farm building bears date 1673, but the street as a whole cannot compare with Heeren Street. This street has a distinctive character entirely its own. It is long, supposed to be straight, is undoubtedly narrow, and formed of two rows of Chinese houses, of which the second row backs onto the sea and is built out on piles.

The architecture of the street is difficult to describe. Suffice it to say that each house is a long narrow box, whose front on the street is a verandah closed-off from next door by a partition of brick. The partition usually has a window in it, round, oval or square in shape, and the front of the house is sure to be either painted with Chinese pictures or carved or adorned with pottery figures.

Not all the buildings are private dwellings. Some are temples. There is not one building like another; they differ in width, in depth, in height, in design, in colour, in ornament. Yet withal they form such a harmonious collection that the eye is delighted with their diverse similarity. Heeren Street is the Park Lane of Malacca, for none but the richest of Chinese live here.

The Stadthaus lies open for inspection, but hardly possesses much of interest for a visitor. There are a few pieces of carving visible, especially the ceiling, brought from Holland, in the Land Office, and an extraordinary collection of chairs, of old pattern and perhaps old actually, in the Supreme Court room.

These are paralleled in Christ Church, where is has been the practice for centuries for each worshipper to bring his own chair. A Chinese carpenter in Malacca, if you order a chair of him and give him no directions, will produce one of these old-fashioned shapes.

Alongside the Stadthaus is a Makara, a monster of Hindu mythology, the sole surviving relic of the time when the Ruler of Malacca was still a Hindu and should date from 1403 or earlier. It is therefore the oldest work of men’s hands in Malacca.

Christ Church possesses some remarkable silver vessels:

A pair of silver communion cups, one presented by the ship Mermaid, with hall-mark attributed to Batavia, and dated 1750

. A silver dish, also Batavian, ten inches across, of the same date

. A silver inkstand, with inkwell and sandbox, of ancient date

. A plain heavy silver chalice of local work of the English period

. A pair of silver salvers, believed to be Dutch, twelve inches square

. A pair of round dishes, Madras work, probably presented to this church by the Dutch in India, repoussé, covered with figures of Indian animals, the centre a snake, very curious

The church is always open and its possessions are shown, for a small fee, to visitors

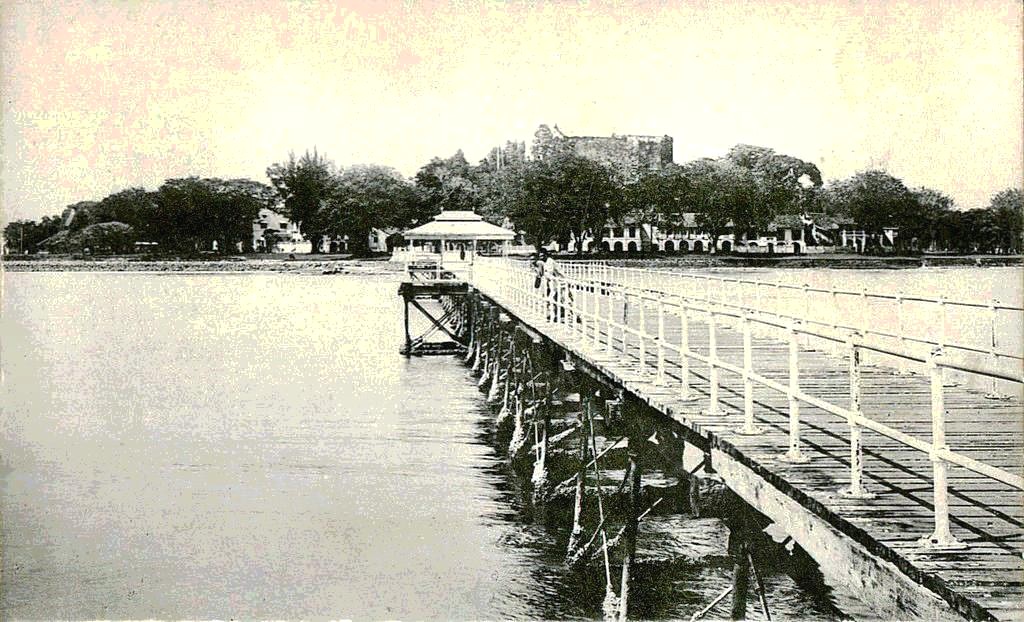

Leaving Christ Church and continuing along between the river mouth and the hill, passing the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank, and the new harbour works out to sea, we reach the jetty. If it be still standing (at this moment its fate is doubtful) the view from the seaward end gives that beautiful panorama of Malacca from the sea which has at all periods delighted travellers.

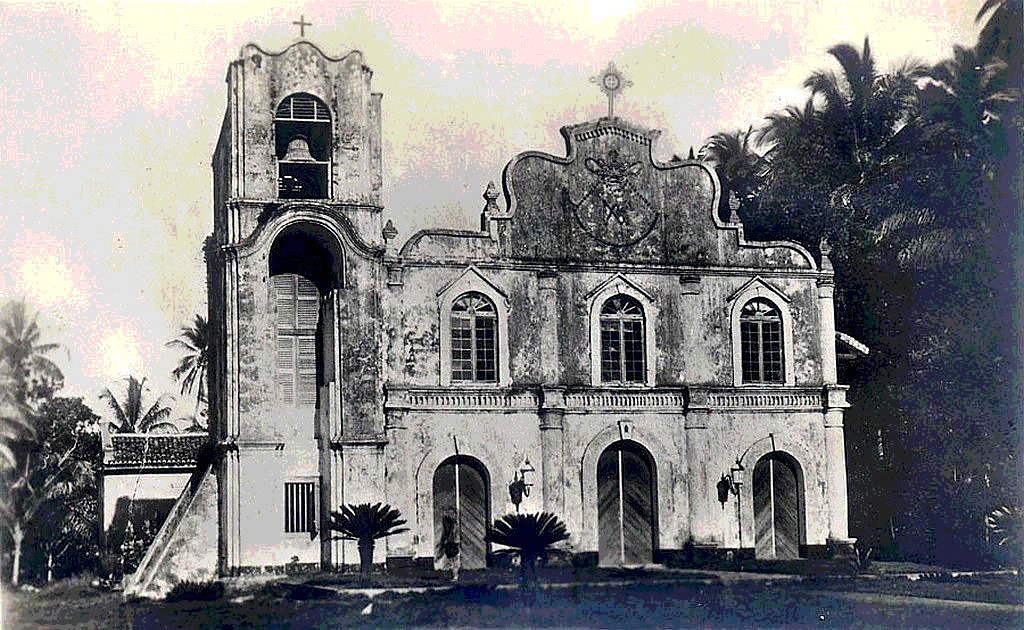

The Portuguese Church of Saint Peter, outside the town on the way back from Bukit China, is believed to be almost coeval with the fortress. It contains, however, but few relics of the past, except its two holy water stoups of antique design and of a stone, which can also be found in the Stadthaus, of a kind not native to Malaya.

The date on the bell is 1698, and it bears a Latin prayer. It is to be regretted that the church has been so lavishly whitewashed inside that the only traces of the frescoes which it once possessed are on the pillars. It may be that the coats of whitewash conceal and perhaps preserve frescoes more elaborate than those whose vestiges are visible.

Most of the above photos are sourced from the website of R.S. Murthi.