A step back in time — the historic Kuan Yin temple of Klang

Published on January 19, 2020 | by nst.com.my

GROWING up in Klang, I’ve witnessed how the royal town’s landscape has shifted and changed over the course of time. As the years passed by, housing estates replaced plantations and green wilderness, new buildings rose up and in their shadows, pre-war shophouses, old temples and other ageing curiosities shrivelled and faded. Changes are unavoidable of course, but seem to come at the expense of old ways and history. We nevertheless learnt to adapt and move along with the inevitable tides of change. Yet truth be told, I miss my old Klang. The one I grew up in.

Thankfully, there are those landmarks that still stand proudly and defiantly in the wake of those changes. I’ve been passing the old Kuan Yin temple every day for decades. The colourful temple that stands by a bustling road leading into Jalan Raya Barat and Teluk Pulai looms bright and colourful within my peripheral vision, as I take that familiar route to work every day.

“I must stop by there soon,” I murmur to myself each time I catch sight of the intricate gilt carvings of the roof. On many occasions, the grandeur of the festivities that goes on at this temple has seen the road outside clogged with traffic, with hordes of devotees making a beeline through the imposing Chinese-style gates. Makeshift stalls jostle for space by the side of the already narrow road selling everything from joss sticks to miniature Kuan Yin statuettes.

Modern Klang overlays — a curious amalgam of multi-ethnic sensibilities, traffic jams, modern malls and Bah Kut Teh — cannot disguise the town’s compelling spiritual seam. From mosques to temples and churches, the royal town’s sacred realm where strong spiritual beliefs and the natural world converge has no shortage of places of worship — some even standing serenely side by side.

At one spot, there’s a temple, mosque and a church located within walking distances of each other. There’s no better representation of unity that this, and that — if you’ll pardon the typical Klang pun — is much to “crow” about.

While the curlicues and carvings of this particularly lively temple have long fascinated me, I’m a little intimidated to enter on my own. Not because I’m of a different faith, but the mere thought of walking into a place of worship clutching my camera makes me feel somewhat like an interloper trespassing into the sanctity of a holy place.

“Don’t worry about that,” assures Wong Fee Jin, who with Chow Hoong Fai are part of the enthusiastic group of guides who’ve formed Jalan-Jalan Klang, a tour group passionate about promoting Klang, its culture and rich history. Her wide smile is comforting as I hesitantly step past the distinctive bright red gates.

WALK BACK IN TIME

With the sequence of halls and buildings interspersed with a breezy open-air courtyard, this temple exudes a surprisingly welcoming presence. The roofless courtyard allows the weather to permeate within the temple and permits qi (the life force central to Taoist worldview and practice) to circulate, dispersing stale air and allowing incense to be burned. It’s somewhat strange to note that the bustling traffic surrounding the temple can be barely heard. No honks, no purring engines — all the outward chatter of noise associated with main roads seems strangely muffled.

Instead, the sweet smell of incense and the tinkling of bells drift through the wide open space of the courtyard. We’re not going to the main temple yet, Wong informs me, as the serious-looking bespectacled Chow walks ahead to a smaller adjoining structure at the side of the main temple entrance. “This is the original temple,” he announces.

By ‘original’, Chow means that this slightly smaller structure (as opposed to the imposing newer pavilion that houses the main deity — Kuan Yin, Goddess of Mercy) is the actual 128-year-old temple that’s been declared a historical landmark in Selangor. “It was relocated three times,” explains Wong.

Established in 1892, the original location of the temple built by Chinese immigrants was believed to have been somewhere near the Klang railway station. “The exact location wasn’t known but it’s believed to have been erected somewhere along the old Kota bridge and the railway station,” she says.

Until the construction of Port Swettenham (now known as Port Klang) in 1901, Klang remained the chief outlet for Selangor’s tin. Its position was enhanced by the completion of the Klang Valley railway to Bukit Kuda in 1886, which was then connected to Klang itself via a rail bridge, the Connaught Bridge, completed in 1890. In the 1890s its growth was further stimulated by the development of the district into the State’ leading producer of coffee, and later rubber.

As such, thousands of Chinese people — most of whom hailed from the Fujian province of Mainland China — settled in Klang to fill labour shortages in tin mines, plantations and railway construction. Fleeing poverty and repression, these immigrants brought their gods and goddesses with them — carrying a bit of the sacred incense or a statue from their local temples — to consecrate a temple in their new home.

Communities were soon formed and places of worship were built. It was around this period that the Kwan Yin temple was established by the Fujian community. “It wasn’t a temple like this,” she remarks, waving her hand at the remarkable colourful structure in front of us. The temple back then, she explains, was a simple pavilion structure — a far cry from the beautiful and intricately carved house of worship that it is today.

The temple was later moved to what is now the Sultan Abdul Aziz Royal Gallery, located next to the post office at Jalan Stesen. This place here in Jalan Raya Barat, she tells me, is the third and final relocation of the old temple from Jalan Stesen. “There’s a stone tablet over there,” she reveals, pointing into the entrance of the old temple, “which we think was brought over from its second location in Jalan Stesen.”

The temple is known as a “pavilion”, a nod to its humble origins. “The locals still call this temple “Kwan Imm Ting”. Ting means pavilion,” explains Wong, smiling. The signage hung over the temple entrance, she points out, shows the date the temple was established. “The year 1892 is written in Chinese,” Wong informs me, pointing to the red and gold sign, before musing: “This could be the old signage that was brought over from the original pavilion.”

LOST IN TIME

The old temple has a traditional pagoda-style exterior and a stark modern space within. Laminated pine arches form the background for precious artefacts, most of which has been moved to the main newer building. What remains are two statues of Buddha smiling benevolently in the quiet space.

There’s an air of disuse that pervades the silent hall. “It’s mostly used as a storage area,” mentions Chow half-wistfully. Piles of boxes and discarded decorations pile in corners, and while the main sanctuary is usually abuzz with devotees, this hall stands empty and silent.

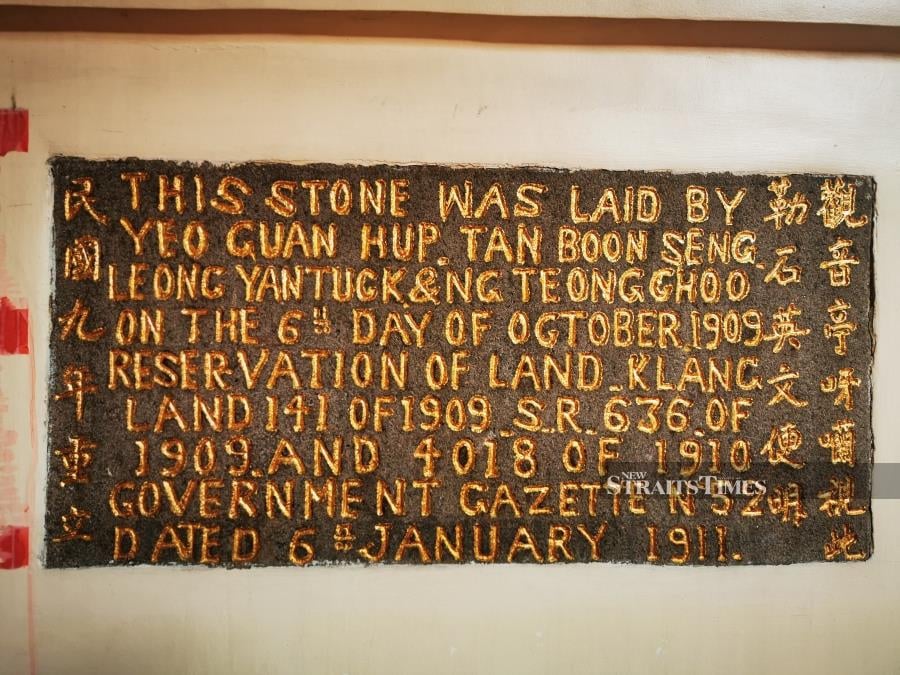

The original tablet which the guides believe was taken from the second location lies half hidden, buried beneath detritus. “Because of its less than auspicious placement here, a replica of the signage was built into the wall over there,” says Chow pointing to an engraved panel on the wall at the side of the altar. The signage depicts the title of the land bestowed by the government for the community to build their place of worship in 1909.

Low chanting set to music wafts through the hall, and while it retains a sense of forlornness, the smiling faces of the Buddhas lend to the preternatural serenity that floods the space.

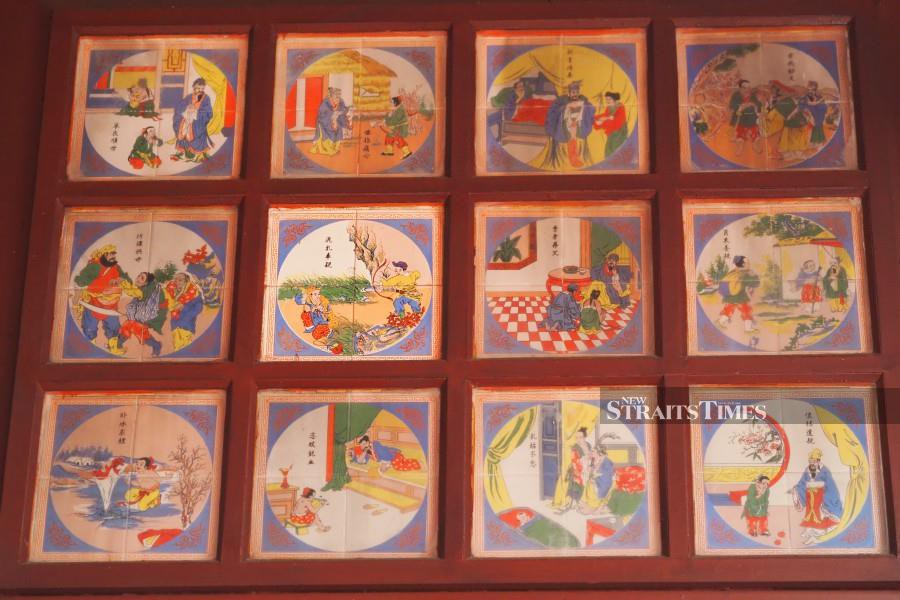

“Look up there,” urges Wong, and up high on the wall just beneath the ceiling, are beautiful hand-painted panels showcasing the Twenty-Four Exemplars by author Guo Jujing during the Yuan dynasty.

These panels depict pictures from Guo’s classic text of Confucian filial piety and were used to teach Confucian moral values. “Filiality, or filial piety (xiào) is the guiding value permeating all aspects of Chinese society,” murmurs Chow as we gaze upon the panels.

On one painting, a young man is surrounded in a cloud of mosquitoes while his parents sleep soundly. Chow tells me the story in a low voice. When Wú Měng of the Jìn dynasty was eight, he was very filial towards his parents. The family was poor, and the bed had no mosquito net.

Every night in summer, mosquitoes in droves nibbled at their skin and sucked their blood without restraint. Although there were many, Měng didn’t drive them away, lest in leaving him they bite his parents. So great was his love for his parents!

Paintings of old stories, legends and fables of Chinese history as well as mythologies adorn the temple building. The building of the temple was funded by the community and they engaged traditional artisans and masons all the way from China who incorporated both traditional Chinese and local motifs, as a nod to the community’s ties to their adopted home.

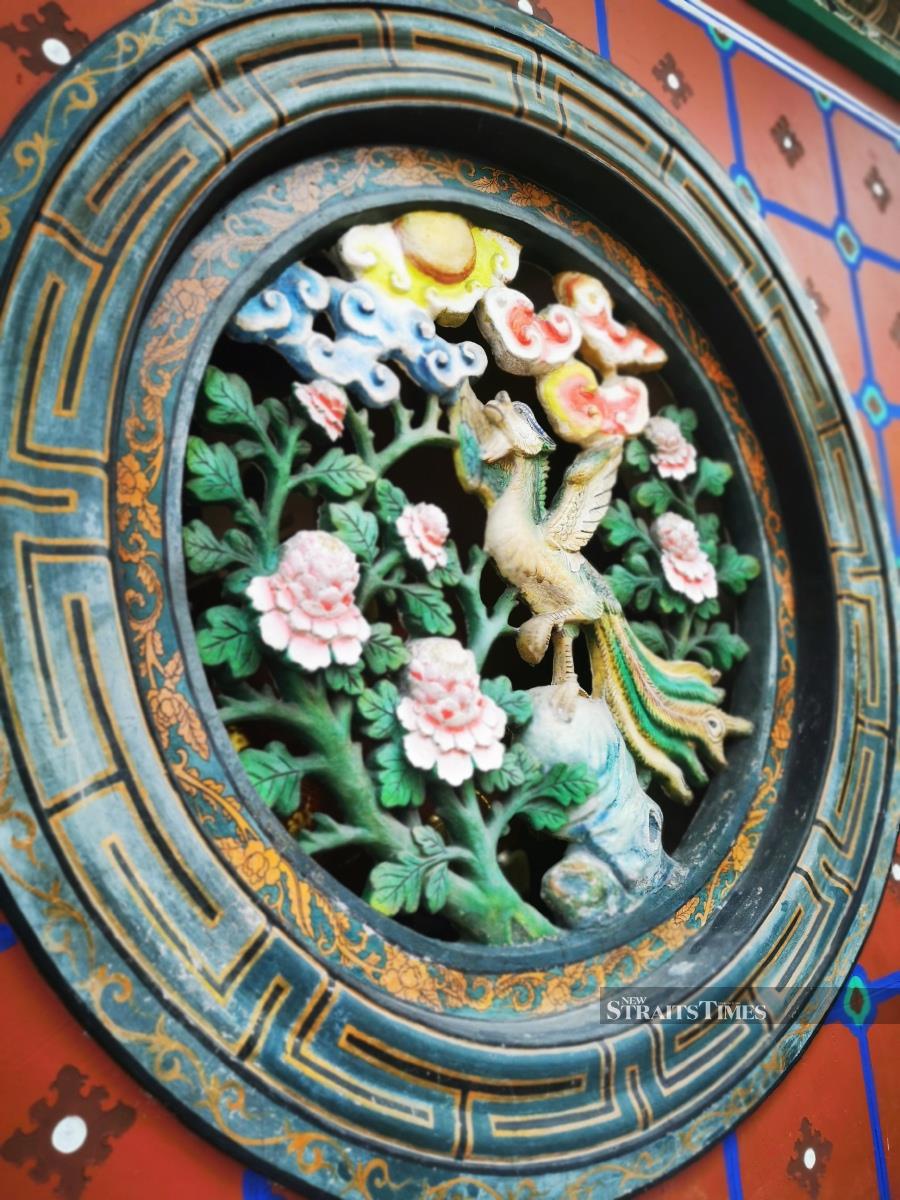

“Can you spot the local motifs on the roof?” asks Wong, grinning. I look hard at the intricate carvings of phoenix, peonies, deers and dragons that glint in the bright afternoon light — and gasp. “I see a durian and a pineapple!” I exclaim in wonderment, and Wong laughs in delight before replying: “You got sharp eyes!” The ceramic ornaments (handpainted to beautiful detail), depicting mythological creatures and motifs were traditionally placed on the terra cotta roof of the temple as protective guardian-figures.

Two stone-carved lions guard the entrance of the temple. “Do you know which is male and female?” asks Wong teasingly. The Chinese or Imperial guardian lions are traditional Chinese architectural ornaments. Typically made of stone, they’re also known as stone lions or shishi.

The concept, which originated and became popular in Chinese Buddhism, features a pair of highly stylised lions — often one male with a ball and one female with a cub — which were thought to protect the building from harmful spiritual influences and harmful people that might be a threat.

This old temple was almost demolished at one time, recalls Chow. The building was infested with termites and had been condemned for demolition — until the current Sultan of Selangor, Sultan Sharafuddin Idris Shah intervened.

The Sultan declared the temple as a heritage site and a book published by His Royal Highness to mark his coronation in March 2003 included the temple as one of Selangor’s historic landmarks. Funds soon poured in and the temple was restored to its former glory.

STEPPING FORWARD IN TIME

“Let’s go look for the original Kwan Yin statues,” beckons Wong as we walk towards the main grand temple. The original statues, she’s referring to, are the wooden carvings that once adorned the older temple and have now been moved to the newer adjoining site.

The newer temple is a fairly large one (built in 2009) sitting on a large compound with an entrance pavilion leading to the main pavilion that takes centre stage. On the other side of the vast courtyard lies a serene Chinese garden complete with a Koi pond and beautiful statues.

The main temple here is a lively place, filled with smoky incense and cluttered with offerings of fresh fruits, vegetarian food and flowers to be used by those in the world beyond.

Unlike the older temple, the grand worship hall is built with figures and mythological creatures inlaid in granite. “The newer temple feature Northern Chinese-style architecture while the older temple leans towards designs favoured by the Southern Chinese,” Wong tells me as we walk up the stairs.

While the temple remains by large a Buddhist enclave, it’s still a homey mix of Buddhist and Taoist deities who often share space with literary and folk heroes the local worshippers have come to revere. A large golden smiling Kwan Yin takes centre stage in this elaborately decorated temple, with two other deities on each of her side.

At one side, there’s the goddess Mazu or Matsu, the goddess of the sea, whom Chinese immigrants prayed to hundreds of years ago when they first set out to make the perilous, often secret trip from mainland China across the seas to their adopted homeland, Malaya. “She’s also revered by fishermen and sailors,” adds Wong softly, referring to Klang’s close proximity to the port.

On the other side, presides the black-faced deity Fa Zhu Gong who’s worshipped for his readiness to help those in need, particularly for his superior prowess to drive out devils and demons from possessed people and ending their woes. “This is the local deity for the Fujian community,” explains Chow.

The temple is open from early morning until late at night, providing cool communal spots full of devotees of all ages. In the courtyard of the temple, incense burners are filled with scores of burning joss sticks flooding the entire courtyard with sweet fragrance.

The bustle of the temple is punctuated by a frequent clicking sound as worshipers who have questions for the gods kneel before the altar and throw crescent-shaped divining blocks on the stone floors. Depending upon how the shapes land, the gods have answered yes, no or maybe. “Most believers come here seeking for wisdom and direction from the gods,” explains Chow in a low voice.

The older Kwan Yin figurines believed to be from the old temple of yore, stand at the base of the larger deity set in gold. For a while, we gaze in silence at the main altar. The ancient wooden carved figurines gaze back serenely at us and the worshippers entering the hall in reverent silence.

The golden hue of the larger-than-life Kwan Yin bathes the temple in an ethereal glow. Muted prayers and supplications are offered and the gods look on benevolently. Time stands still here and for a moment I feel I’m transported back into the era where trishaw peddlers roamed the streets during British colonial days. Faith, as they often say, is transcendent and I’m inclined to agree.

I’m also beginning to think that in some ways, I’m wrong. Klang’s ancient ways aren’t dead; it is being reborn in odd corners of the city and in unexpected ways. It’s not the same as the past, but still vibrant and real — ways of life and belief that echo bygone days.

Jalan-Jalan Klang comprises a group of guides who are passionate about Klang. For more information about their walking tours around Klang town, go to www.facebook.com/JalanjalanKLANG.

The Federal Government then bought the palace in 1957, to be converted into the Istana Negara. Since then it had undergone several renovations and extensions. But the most extensive upgrading was carried out in 1980, as it was the first time that the Installation Ceremony of His Majesty Seri Paduka Baginda Yang di-Pertuan Agong was held at the Istana Negara. Prior to this the Installation Ceremonies were held at the Tunku Abdul Rahman Hall in Jalan Ampang, Kuala Lumpur.

This majestic building is nestled within a serene and beautiful 11.34-hectare compound with a variety of plants and flowers, swimming pool and indoor badminton hall. It is located at Syed Putra Road right in the heart of the capital of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur. The building has several halls for specific purposes such as the two main halls, the Throne Hall (Balairong Seri) and the Audience Hall (Dewan Mengadap) on the ground floor.

The whole area is fenced up and the Royal Insignia of His Majesty is placed on each steel bar between two pillars of the fence. At the front of the Istana Negara, there is the main entrance which resembles a beautiful arch. On each side of the arch, are two guard posts to shelter two members of the cavalry in their smart full dress uniform similar to the ones at Buckingham Palace, London.

As the palace grounds are not opened to members of the public or tourists, the Main Palace Entrance is a favourite picture spot for tourists.